A Language None of Whose Words is Known To Me

Hugo von Hofmannsthal's "Letter of Lord Chandos"

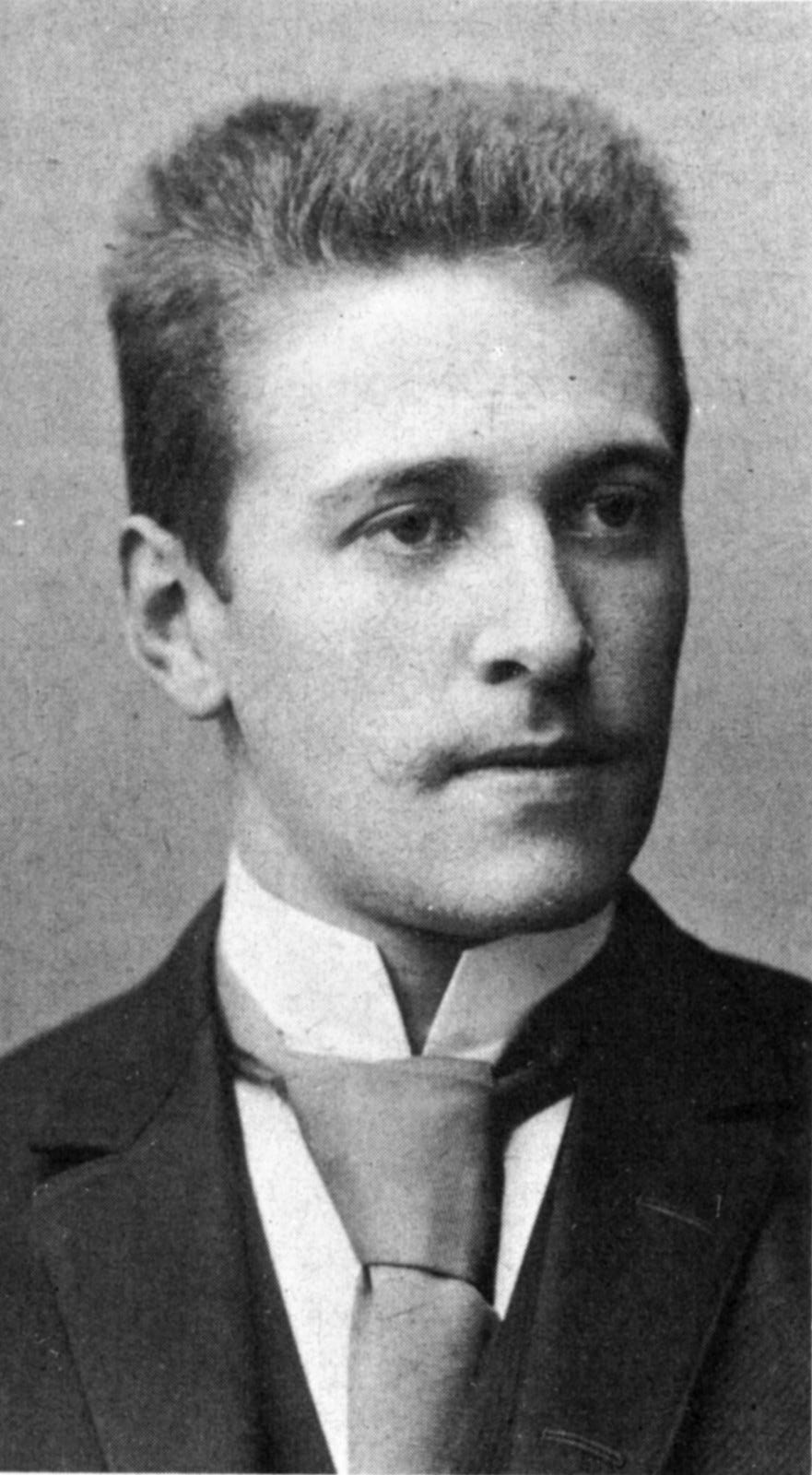

We’ve begun our read-along of Stefan Zweig’s The World of Yesterday, and over the weekend I’ll be posting on its second chapter, about Zweig’s school days. I will probably not write about one of its most memorable scenes: the legendary explosion of the young Hugo von Hofmannsthal upon the Viennese literary scene. Under the pen name “Loris,” the 16-year-old von Hofmannsthal had been publishing some of the finest lyric poetry in German since Goethe. People were amazed—as Zweig so wonderfully describes—to discover that the author of this accomplished poetry was a mere teenager.

Since I won’t focus on von Hofmannsthal this weekend, I thought it might be nice here to discuss one of his most famous essays, “The Letter of Lord Chandos.” The “Chandos Brief” has a mythic aura of its own: its fictional author describes a crisis that has left him unable to write. Though the precise relationship between life and art is elusive, this description has autobiographical elements. Von Hofmannsthal himself was undergoing a similar crisis of his own. Indeed, he subsequently wrote very little poetry—in that sense, the essay seems prophetic—turning instead to very different endeavors, such as collaborating with Richard Strauss on a number of operas and founding the Salzburger Festspiele, which continue to this day.

“The Letter of Lord Chandos” is not only one of the great documents of literary modernism, it also—in ways I will try to indicate below—provides a kind of symbol for the entire Viennese fin de siècle that produced it. It’s short, only about a dozen pages; interested readers can find an English version online here. Let’s take a look….

Let me begin with two sentences from the Chandos Letter: its most famous line and an evocative sentence from its conclusion that, I will suggest, announces an artistic agenda for its era.

“My case, in short, is this: I have lost completely the ability to think or to speak of anything coherently.”

“…neither in the coming year nor in the following one nor in all the years of this my life shall I write a book, whether in English or in Latin: and this for an odd and embarrassing reason which I must leave to the boundless superiority of your mind to place in the realm of physical and spiritual values spread out harmoniously before your unprejudiced eye: to wit, because the language in which I might be able not only to write but to think is neither Latin nor English, neither Italian nor Spanish, but a language none of whose words is known to me….”

The (ostensible) author of these lines is one Lord Philip Chandos, who pens them in a letter written (ostensibly) to the English statesman and philosopher Francis Bacon on 22 August 1603 (the year in which Bacon was knighted, as it happens). He is replying (ostensibly) to a previous letter from Bacon inquiring why his friend Chandos had ceased writing books.

Chandos’s reply, explaining his literary silence, is very carefully structured: first, a description of his earlier work, before the crisis hit; then a description of the crisis itself; and finally an account of the condition in which the experience has left him. The letter’s fascination lies especially in the strange crisis— “I have lost completely the ability to think or to speak of anything coherently”—but in order to understand it, we need to pay attention to each of these stages. What has happened to Chandos is confusing, but if we can puzzle it out, it provides a window onto the entire intellectual and artistic world of the early 20th century.

Chandos first describes his earlier works and the plans he’d had for the future. He had written pastorals with titles like The New Paris and The Dream of Daphne, as well as what appears to be a treatise on Latin prose. He planned a history of the early reign of Henry VIII; a study of classical myths and fables; and an Apophthegmata, a collection of maxims, ancient reflections, historical marvels, and artistic achievements. The latter was to bear the title Nosce te ipsum—“know thyself,” the famous inscription from the Delphic Oracle.

At every stage of the Letter we need to pause and ask ourselves what von Hofmannsthal is up to. What is important about these earlier works or projected works? What links them together? They are steeped in classical learning; they strive after order, structure, and harmony. Encyclopedic in ambition, they see the world as unified; every part of the whole has its place and is connected to every other part. As Chandos writes, he “conceived the whole of existence as one great unit.” He feels himself at one with this vast harmony, with “the whole expanse of life in all directions; everywhere I was in the centre of it.” His mind perceives the rational order underlying all things and is itself an ordering power, “capable of seizing each [door] by the handle and unlocking as many of the others as were ready to yield.”

But that harmony has been shattered, as Chandos abruptly states in the first sentence I quoted above: “I have lost completely the ability to think or to speak of anything coherently.” The process begins when Chandos finds himself no longer able to grasp or employ general, abstract, or universal ideas like “spirit, soul, or body.” Abstract terms “crumbled in my mouth like mouldy fungi.” (Not a bad phrase for a guy who can no longer write!) He therefore becomes incapable of reaching judgements or making moral evaluations, because these rely on universal moral abstractions. In a striking example, he cannot explain to his daughter why she should always tell the truth. Whereas before the world had been a unified whole, now “everything disintegrated into parts, those parts again into parts; no longer would anything let itself be encompassed by one idea.”

What exactly has happened? Let me sidestep that question for a moment to explore Chandos’s description of his present condition, which may provide clues to help interpret his experience. A peculiarity of his post-crisis state is that it includes moments mirroring his starting-point, when the world hung together as a unified whole. In these moments, “something entirely unnamed, even barely nameable … reveals itself to me, filling like a vessel any casual object of my daily surroundings with an overflowing flood of higher life.” He speaks of these moments as offering sensations of “the Present,” of “Infinity,” of “immense sympathy.” When he is seized by one of them, he writes, “Everything that exists, everything I can remember, everything touched upon by my confused thoughts, has a meaning.” It is “as if we could enter into a new and hopeful relationship with the whole of existence if only we begin to think with the heart.”

The crucial difference between these moments and his earlier experience seems to be that the current revelations are not under his control. Chandos does not know when the experience might strike or what might cause it; he cannot summon it up at will. If his younger self perceived the order of the cosmos and actively recreated it in his art, the post-crisis Chandos can only passively await the flash of insight that a chance object or event reveals to him—and, having experienced it, he cannot adequately recapture the moment in words.

Again: what exactly has happened? To understand Chandos’s puzzling experience, we need to play the detective a bit. Two clues strike me as especially helpful. The first is the letter’s addressee. Von Hofmannsthal could have chosen anyone—or have created a fictional person—to be the recipient of this letter. He chose Francis Bacon. Why?

Bacon had a long and influential career in both philosophy and politics, but he is best known to us as the creator of the scientific method: the slow, inductive approach that eschews first principles and instead seeks gradually to build up what knowledge we can, step by step, through careful observation and experimentation. Its analytical approach is a kind of intellectual solvent; just as it breaks the world down into atoms (and atoms into their component parts), so too does it substitute particular observations for universal generalizaions. Every general law is subject to refutation by the next experiment; all knowledge is provisional.

By having Chandos write to Bacon, surely von Hofmannsthal is signaling something about the effects of this process by the turn of the 20th century. When Chandos writes that “everything disintegrated into parts, those parts again into parts,” he is expressing a kind of psychological anguish at the world’s lost wholeness. It is as if the world had been subjected to a process of dissection, almost like the opening lines of T. S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” which speak of “the evening spread out against the sky / Like a patient etherized upon a table.”

And the second clue? One of the Letter’s most striking features is an enormous irony crying out for explanation. Chandos claims that he can no longer speak of anything coherently, but he nevertheless writes a remarkably eloquent letter explaining his state, frequently generating rhetorically striking images to help convey it. The line about “mouldy fungi” is only one instance of this among many. Those who know the essay will remember Chandos’s nightmarish vision of poisoned rats writing in the agony of their death throes, an image so vivid that no one who has read it is likely to forget. But here are three particularly lovely examples of Chandos’s skill with words, which he has apparently not fully lost.

After referring to the unnameable feeling that fills casual objects with a “flood of higher life,” Chandos offers Bacon some examples: “A pitcher, a harrow abandoned in a field, a dog in the sun, a neglected cemetery, a cripple, a peasant’s hut—all these can become the vessel of my revelation.”

“In these moments an insignificant creature—a dog, a rat, a beetle, a crippled appletree, a lane winding over the hill, a moss-covered stone, mean more to me than the most beautiful, abandoned mistress of the happiest night.”

“My unnamed blissful feeling is sooner brought about by a distant lonely shepherd’s fire than by the vision of a starry sky, sooner by the chirping of the last dying cricket when the autumn wind chases wintry clouds across the deserted fields than by the majestic booming of an organ.”

It is noteworthy, I think, that all these examples have what I can only call an autumnal feel, a sense of things passing away. (I especially love that last one: it is not only a cricket, but a dying cricket, indeed the last dying cricket; not only a wind but an autumn wind; not only clouds, but wintry clouds; not only fields, but deserted ones. Talk about pouring it on!) But what seems to me even more important is that whenever Chandos seeks to convey his current state and the peculiar sensation of wholeness that unpredictably descends upon him, he can resort only to images—clear, concrete, visual images of particular objects.

My experience of the world—like yours, like everyone’s—is always particular and invidual. If I want to describe it to you, I normally resort to language, putting it into words that match some experience of your own. Language, of necessity, always generalizes. Even the simplest words—table, bread, cat—are abstractions from lived reality. (Try imagining a cat—you can only picture some particular cat, not “catness” as such.)

But Chandos lives in a world that has dissolved, “disintegrated into parts, those parts again into parts.” At the end of that process, it appears, even language itself has disintegrated into parts. Chandos can no longer tell Bacon what he is experiencing. He can only show him, hoping that perhaps these images will summon up some matching version of his own revelation, restoring a sense of universal harmony and wholeness.

This brings me back to the second quotation with which I began, a passage that reverberates widely through the period. Chandos will never write another book, he says, because “the language in which I might be able not only to write but to think is … a language none of whose words is known to me.” With his visual imagery and flashes of sudden insight, Chandos—and von Hofmannsthal—is in search of a whole new language, one that could replace the language that no longer seems adequate to his needs, because its abstractions do not correspond to the particularity of lived experience.

I close with a final note about the context. Von Hofmannsthal’s suggestion here of the search for a new language, one whose words are not yet known, is for me a kind of distillation of the feverish creativity that marks Vienna at the fin de siècle, a metaphor for the entire age. In one field after another, we see extraordinary artists searching for a new language: a literary language in the case of von Hofmannsthal, Arthur Schnitzler, or Karl Kraus; a visual language for painters like Gustav Klimt or Egon Schiele; a musical language for Gustav Mahler, Arnold Schoenberg, or the Second Viennese School; an architectural language for Otto Wagner and Adolf Loos; a psychological language for Sigmund Freud; a philosophical and scientific language for Ludwig Wittgenstein and the Vienna Circle.

All of them, in their distinct ways, are striving to convey meaning in “a language none of whose words is known to me.”

As always, thanks for reading, and I’ll see you next time for another installment From My Bookshelf.

And if you’re intrigued about the various figures I just mentioned and others like them… join our ongoing Stefan Zweig read-along! ; )

When I first saw Jedermann (Everyman) in Salzburg, I thought von Hofmannsthal had stolen it from the 15th century morality play Everyman (in which I played the role 'Good Deeds' in college). I've since learned it was based on that work. along with two Dutch morality plays and a work by Hans Sachs whom Wagner immortalized in The Meistersinter of Nuremberg.

I've been reading a lot about von Hofmannsthal in Count Harry Kessler's diaries. The two were extremely close for a long time, traveled together to Greece. Von Hofmannsthal often visited Kessler in Weimar and Berlin. Kessler brought von Hofmannsthal the story for Der Rosenkavalier, based on a French play he had seen (Kessler lived in Paris, too) For days the two worked together on the narrative structure for the opera, scene by scene, but when the opera premiered, Kessler's name was omitted. It ended their very long friendship.

The Chandos dilemma seems headed toward a Wittgenstein-like conundrum. I think of his line, "The limits of my language means the limits of my world." from Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus 20 years after 'Letter. . .'