111,078. Many of you, I’m sure, have been awaiting an odometer update following my two weeks of family chauffeur duty. As reported in my earlier post, “Carless and Free,” I began my duties around noon on Monday, August 4, with the odometer showing 109,726 miles. When I finally wrapped up those two weeks of driving at about 6pm on Friday, August 15, it read 111,078. So I managed to drive 1,352 miles (that would be 2,175 kilometers for my European readers) in just under two weeks, without even the pleasure of taking a vacation! Hence my nostalgia for Europe’s public transportation—the books I might have read during those 1,352 miles…!

Today’s post will be the first of a two on a new author. The book under discussion is conveniently divided into two parts, so I’ll discuss Part 1 today and will return for Part 2 later. Enjoy!

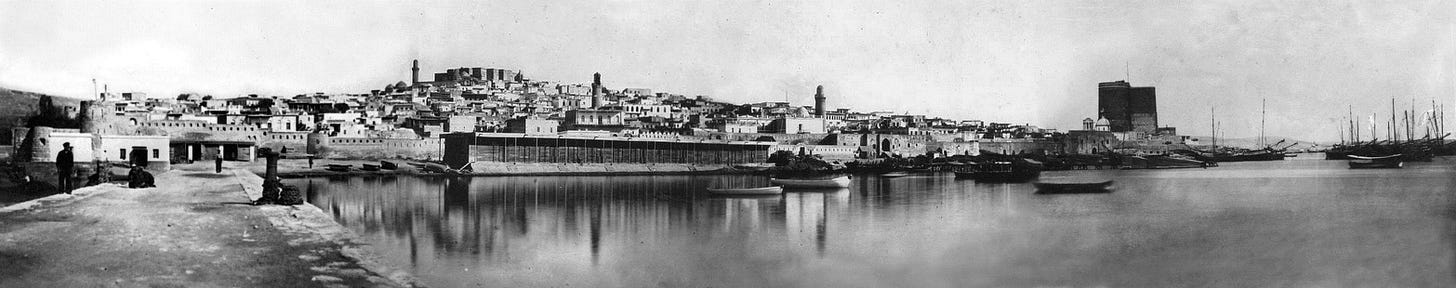

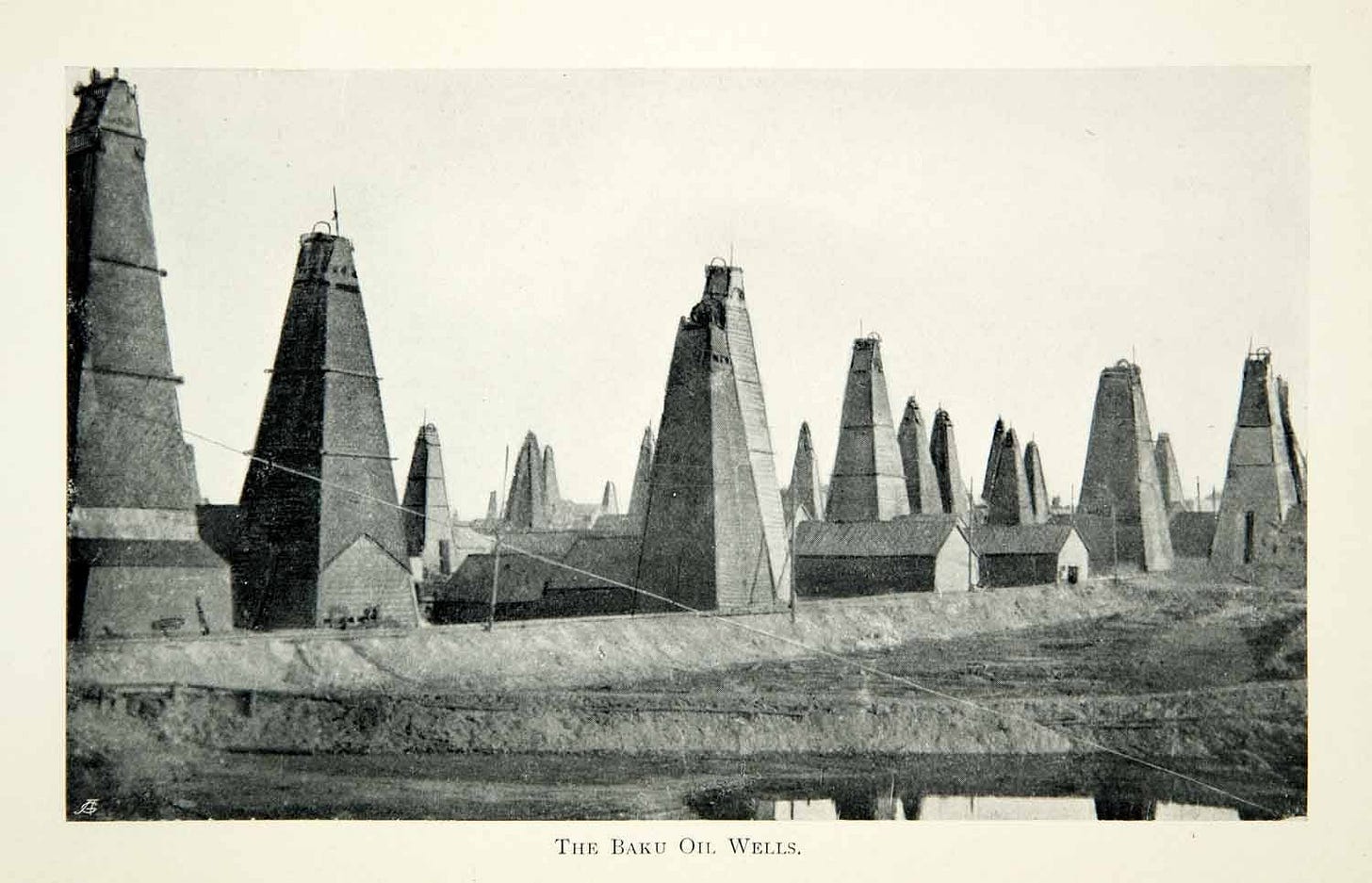

Earlier this year I discovered Teffi, a Russian exile from early in the 20th century who ended up in Paris and wrote movingly of the world she had left behind. Now I have found another female voice from the same time and a related place: Banine. The daughter of a wealthy Muslim family of oil magnates in Baku, Azerbaijan, Umm-El-Banine Assadoulaeff was forced to flee when the Soviets took over at the end of World War I. Days in the Caucasus (translated from the French by Anne Thompson-Ahmadova) describes this early part of her life. Eventually, Banine found her way to Paris, where she converted to Catholicism and became a writer, closely networked with many of the prominent cultural figures of her era.

I will reserve final judgement until I’ve finished the book, but Part 1 of Days in the Caucasus has me eager for more. If Teffi’s stories are often tinged with melancholy, Banine is witty, mischievous, and irreverent. Though she describes herself as a bookish and often shy child, the woman who emerges in these pages is charming and vivacious. One imagines that she must have been the life of every party and the center of attention in every conversation.

Banine’s portrayal of her childhood in Baku are delightful, offering a glimpse inside a prosperous Muslim family just over a century ago, on the border between eastern Europe and central Asia, where Christianity, Islam, and Judaism intersected, as did multiple languages and nationalities: Turkish, Persian, Azeri, Armenian, Russian, and more. The earliest memories she recounts go back to her childhood, under the watchful care of Fräulein Anna, the German Christian governess who raised the children when their mother died shortly after Banine’s birth. Anna’s place in the family was somehow both tenuous and secure: tenuous because her religion and ethnicity made her an outsider, secure because of her genuine love for her young charges. “Surrounded by a fanatically Muslim family,” writes Banine, “in a city that was still very oriental, she managed to create and maintain an atmosphere of Vergissmeinnicht [forget-me-not], of sweet songs for blonde children, of Christmas trees with pink angels, of cakes heavy with cream and sentimentality.” Anna’s influence wanes as the children grow older, and Banine regrets having not always returned her love as it deserved; still, she remembers, “Almost all that was lovely in my childhood was connected with her, or, rather, originated with her.”

The book’s cast of characters also includes Banine’s father, an intimidating presence rather than a loving one. Rich, successful, frequently away on business, he grants his family members a surprising degree of freedom and shrugs off the criticism of relatives with indifference. But he reacts strongly when things stray too far from prescribed Islamic custom, as when Banine’s older sister Leyla runs off with a Russian aviator. (She is quickly found, brought home, and married off in short order.)

Banine’s cousins Asad and Ali weave in and out of the narrative. The impetuous boldness with with they pursue their own interests wins Banine’s youthful admiration. “They were my unrivalled teachers and professors,” she says, “strict, unfair, but magnificent.” They teach her to smoke and to play card games, but their “most advanced skill” was lying: “Excessively liberal in morality, they lied, snitched, told tales and even stole whenever the opportunity arose.”

Two women supply the poles between which Banine’s young life oscillates: her grandmother, on the one hand, and her father’s second wife, Amina, on the other. Grandmother is a towering figure, massive both in bulk and in personality. Banine describes her as enormously fat, handing out orders, spoiling her beloved grandchildren, magnanimously receiving poor relatives who acknowledge her superiority, and pronouncing upon the state of the world as someone who expects her opinions to receive unanimous assent. But she is also a figure from a bygone age, and at a certain level she knows it:

The gap separating her, whose life was a continuation of that of the first Muslim women of the Hegira, from us [grandchildren] was not one of a few dozen years but of fourteen centuries. She wanted to know nothing of the ‘civilizing force’ of the Russians, and did not even know the language, because it was not compulsory when she was young. She saw Russians only as colonizers, secular troublemakers, men of another race and another religion—in a word, infidels—for whom she felt hatred tinged with contempt. Her hatred is easy to understand: the life she loved was slowly disintegrating around her….

Grandmother may be a majestic figure, but she is also a tragic one.

Amina could hardly be more different. She is Muslim, and beautiful, but apart from that, Banine’s new stepmother falls far short of the extended family’s expectations. For starters, “her father didn’t sell anything.” To the contrary, he was only “a common employee.” Worse, he had “raised his two daughters in the European fashion,” sending them to Paris, where they “lived … on their own,” had “moved in artistic circles,” and had even “gone out alone at night with men.” She had already been married once and divorced her first husband.

This “love match with a penniless girl” simply does not fit into the relatives’ worldview. They regard it as “unthinkable, contrary to good sense, good taste, reason, even common decency.” It is one more symbol of the distance between the old era and the new:

The world of my grandmother and aunts was already showing cracks, but this would bring it crashing down. They knew who to blame, reserving their hatred for Russia and Christians, the destroyers of their world.

Banine and her siblings, by contrast, are “overjoyed” at the prospect of Amina’s arrival. She represents progress, the exotic, the modern. Though Banine is ultimately disappointed to discover that her new stepmother, whom she adores and from whom she longs for affection, is not deeply interested in her, she nevertheless glimpses in Amina a world that she yearns to join.

This partial family portrait indicates another of the book’s most intriguing qualities: its depiction of the clash between traditional and modern ways of life. Although this contrast appears in numerous details, Banine reflects upon it movingly in a short chapter halfway through Part 1, a kind of interlude following the announcement of her father’s pending remarriage and preceding Amina’s actual arrival. For Amina’s appearance supplies a kind of caesura, jolting the young Banine into a growing awareness of the difference between the life she has led and the one of which she dreams. In Amina’s presence her family’s traditional life suddenly appears wanting:

At that time a new horizon opened up before me: I realized there were other worlds, not just my small world with Fräulein Anna at its centre and our country house at its boundary. Convinced that Baku was a splendid city, my family irreproachable and our life desirable, I was surprised and saddened to discover that Amina did not share my opinion; Amina despised Baku, loathed the family and rebelled against our existence. I had ‘to reconsider my position’ and came to see Baku as a filthy backwater despite my millionaires, our family as dangerously barbaric and our life as pitiable from all points of view.

Banine further connects these transformations with a decline in Islam. Under the influence of the “sordid millionaires” (many of them her own relatives!) and their wealth, faith had grown more superficial or hypocritical, a facade papering over modernity’s least desirable imports:

Islam had ceased to be true Islam, thereby losing its function. Engulfed by modern life, it no longer brought peace to the soul, only a list of constraints that were thrown off without regret. Is gambling forbidden by the Koran? The whole of Baku played cards, staking enormous sums into the bargain. Is wine forbidden by the Prophet? People made up for it by drinking spirits—vodka, brandy—on the false pretext that it wasn’t wine.

Again, it is perhaps Grandmother—her poignant sorrow mixed with puzzlement and anger—who most sees most clearly that a great change is taking place. As she contemplated her granddaughters, Banine imagines, “she must have felt that her life and those of her peers, primitive and narrowly confined, left less scope for disappointment, while ours, rich in various possibilities, was thereby full of potential pitfalls too. She would have been right: liberty often comes at a heavy price.”

Two of the books charms are thus Banine’s portrayal of her family members and the personal glimpses she offers into the clash of tradition with modernity. A third is the snapshot we get, again through her family’s experience, of the political convulsions that upended whole peoples, regions, and nations during World War I and its aftermath, convulsions in which religious, ethnic, and ideological factors all played a role.

Among Banine’s most disturbing childhood memories, made all the more jarring by her disengenuous recounting of it, is a game that she liked to play with Asad, Ali, and a friend, Tamara, who was half-Armenian. “On holidays,” she writes, “we played at massacring Armenians, a game we loved above all others. Heady with racist passion, we would sacrifice Tamara on the altar of our ancestral hatred.” When World War I begins, however, that ancestral hatred is reversed. Revolution breaks out in Russia, and its “border regions, whose populations did not share the history, ancestry and religion of the Russians, [began] to break away and form independent republics.” In Azerbaijan, a group of Armenians took power and “inaugurated their rule with a massacre of Muslims, who were unable to defend themselves.” Later, of course, when the Turks occupied the country, they “naturally took revenge on the Armenians, massacring them on a large scale” and restoring calm “by hanging some poor wretch almost every day.”

The fortunes of Banine and her family change along with these political upheavals. After kindly Armenian neighbors save their lives, they escape to Persia for a miserable period of exile. The Turkish occupation permits them to return to an Azerbaijan that is simultaneously in crisis—“as happens during troubled times in history, morals were relaxed, and tradition and religion, already badly shaken, fell further into decline”—and also intoxicated with newfound possibilities. With biting irony that anticipates the futility of these hopes, Banine describes a moment of optimism that repeated itself in country after country:

There was talk of an independent Azerbaijan, Armenia, Karelia, Kazakhstan and I don’t know what else: Independent, Autonomous, Proud, Free, and Happy. Epithets accompanied by Republics and Republics combined with epithets rained down on the astounded peoples.

For a brief time, Banine’s own father becomes minister of commerce in the new Republic of Azerbaijan.

It was not to last. Even as everyone expects that the Bolsheviks will soon have to abandon power in Russia, they are of course solidifying their rule and preparing to expand it. As Part I of Days in the Caucasus draws to a close, Banine’s grandfather dies, leaving her a fortune and making a multimillionaire of her at age thirteen. But only, she continues, “for a few days, for I was soon woken at dawn by ‘The Internationale’ sung in the street. I got up and saw soldiers who neither resembled nor wore the uniform of Azerbaijani askaris. It was the Russians.” She concludes with a foreboding assertion: “With my own eyes I had seen the end of a world.”

Days in the Caucasus is—so far—witty, poignant, and moving, offering a fascinating look at a part of the world to which most Americans pay little attention… though it is now acquiring new geostrategic importance. I look forward to reporting back again in a week or so when I have finished Part 2.

As always, thanks for reading, and I’ll see you next time for another installment From My Bookshelf.