It's All About... (ahem, we don't discuss that here)

Zweig and the sexual hypocrisy of fin de siècle Vienna

Somehow my “most terrifying line in Western literature” post from a couple of weeks ago seems to have taken off again this weekend and is pulling in more new subscribers. I am baffled—pleasantly surprised, but baffled—as to why this is happening. But if you are one of those brand-new subscribers, welcome! Today we continue our FMB read-along of Stefan Zweig’s The World of Yesterday, turning to one of its more provocative chapters.

As Microstack readers know, I am traveling at the moment, all the way at the far end of the continent, near San Diego, where I am delivering child #4 for her first year of university study. I wish I could say that it got easier each time, but alas, that’s not the case. The travel and our activities here have left little time for a post this weekend. But I want to share at least a few thoughts on our most recent Zweig reading. Fortunately, this chapter largely speaks for itself….

When my students reach chapter three, “Eros Matutinus,” or “Morning Eros,” they are invariably rather shocked.

In it, Zweig continues the work of the previous chapter on education, further complicating the picture of fin de siècle Vienna that he drew in the book’s opening chapter. If he initially seemed nostalgic for the lost “world of security,” that no longer appears to be the case. Indeed, by the end of chapter three, the accounts are rather finely balanced: “If morality gives man freedom, then the State confines him. If the State permits him freedom, then morality attempts to enslave him. We lived better and tasted more of the world, but the youth of today lives and experiences its own youth more consciously.”

The theme of “Eros Matutinus” is clear and simple: hypocrisy.

Let me point out three ways in which the era’s sexual hypocrisy makes itself felt in Zweig’s description.

The first is most obvious: Viennese society as a whole preserves a exaggerated reticence about sex, almost refusing to acknowledge its existence, while simultaneously conducting a remarkably active clandestine sex life. (I realize that “society” cannot precisely have a sex life, but on Zweig’s telling, it does indeed seem to be almost a collective activity!) Vienna looked upon sexuality, he says, “as an anarchical and therefore disturbing element, which had no place in its ethics and was not allowed to see the light of day.” All social authorities were “united in a boycott of hermetic silence” on the matter. But it did not take the young men of Zweig’s generation long to discover that this was all a fraud. “After all, it was unavoidable that one of the fifty Gymnasium students would occasionally meet his professor in a dimly lighted back street, or that in the family circle we heard that this one or that one, who was particularly haughty in our presence, had various lapses from grace on his conscience.”

This conspiracy of silence about the city’s ubiquitous sexual activity produces two of the chapter’s more humorous anecdotes. On the one hand we have Zweig’s aunt, who suffered quite a shock on her wedding night:

[She] stormed the door of her parents’ house at one o’clock in the morning. She never again wished to see the horrible creature to whom she had been married. He was a madman and a beast, for he had seriously attempted to undress her. It was only with great difficulty that she had been able to escape from this obviously perverted desire.

On the other hand we read about the… shall we say, unusual?… methods adopted by some fathers to introduce their sons to the facts of life:

The family physician was called in, and at the proper time bade the young man come into the room, polished his glasses unnecessarily before he began his lecture on the dangers of venereal diseases, and admonished the young man, who usually at this point had long since taught himself to be moderate and not to overlook certain preventive measures. Other fathers used an even more astonishing method; they engaged a pretty servant girl for the house whose task it was to give the young lad some practical experience.

Suffice it to say that these are not the techniques by which my students have learned about the birds and the bees.

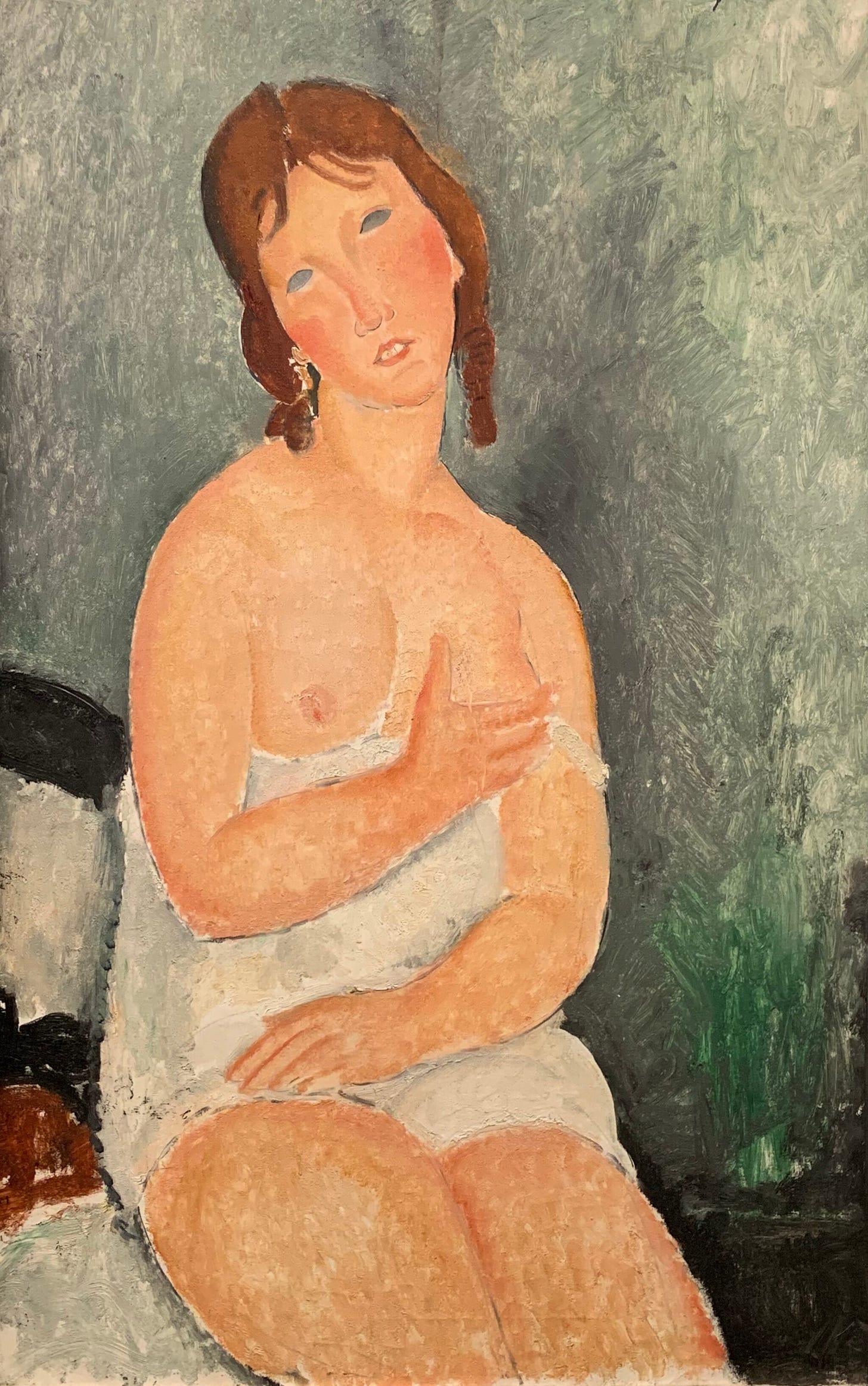

The contrast between those two anecdotes points toward the second glaring form of hypocrisy that Zweig exposes in this chapter: the extraordinary double standard applied to men and women in matters of sexuality. Women were expected to be utterly innocent, ignorant about the most basic sexual matters. Because they had to remain pure, intense chaperoning was required. Even their clothing was highly artificial, enclosing them in rigid layers of garments so that no stray bit of flesh might be seen and as a result practically immobilizing them: “a woman, once she is encased in such a toilette, like a knight in armor, could no longer move about freely, gracefully and lightly. Every movement, every gesture, and consequently her entire conduct, had to be artificial, unnatural and affected in such a costume.”

All this stands in stark contrast to Zweig’s description of men’s situation, and not only with respect to that pretty servant girl. If women’s fashion was designed to cover up the woman—while also, however, accentuating a slim waist and large bosom, and thus drawing attention to the very sexuality it ostensibly sought to conceal—men tried to look older and more masculine than they were, “sport[ing] long beards or at least twirl[ing] a mighty mustache, so that their manhood was apparent even from afar.” While women were kept in ignorance, society “winked one eye at a young man and even encouraged him with the other ‘to sow his wild oats.’” Zweig describes the relation between young men and women as like that between “the hunter and his prey.”

Yet society also frustrated the desires of young men. Because a man was not thought reliable until he had a steady job and social position, marriage—the normal outlet for such desires—was often not possible until long after his sexual drive had been awakened. His options for sowing those wild oats were therefore limited and unsatisfactory: “shopgirls and waitresses … girls of the very poorest proletarian background.”

Or, of course, prostitutes. And here we come to the third striking instance of hypocrisy that Zweig relates: society’s attitude toward prostitution. It is difficult now, he says, to imagine “the gigantic spread of prostitution in Europe before the World War.” In a metaphor whose beauty belies its horror, Zweig says that prostitution “constituted a dark underground vault over which rose the gorgeous structure of middle-class society with its faultless, radiant facade.”

But the hypocrisy in this case was not merely that society preached an ideal of feminine purity while simultaneously allowing, even encouraging, women to sell their bodies. It went deeper than that. For the sake of health and hygiene, Vienna legalized prostitution, thus giving it a veneer of official approval. But these women, now subjected to the further indignity of a medical surveillance regime, remained highly vulnerable—tolerated, but neither approved nor protected. The state’s attitude “towards this shady affair was never a very comfortable one.” Though practicing a “legally approved profession,” prostitutes were nevertheless considered outcasts beyond the law.” For example, “a prostitute who sold her wares, that is, her body, to a man and later did not receive the price agreed upon, had no right to sue him.” Legal authorization undermined by self-serving moral disapproval. Hypocrisy, through and through.

In this chapter more than anywhere else, Zweig peers behind the glitz and glamour of fin de siècle Vienna to show that not everything was as beautiful as it seems. For those of us—like me—who find ourselves drawn to the era, it is a useful reminder.

Let me share two final thoughts that always occur to me when I read this particular chapter. First, is it any wonder that Sigmund Freud should have emerged from the social atmosphere described here? When I wrote about von Hofmannsthal’s Chandos Letter, I mentioned that his vision of a language none of whose words is yet known is a favorite image of mine for describing this era’s energetic creativity, its striving after new modes of expression. My other favorite metaphor for the period is Freud’s image of the psyche: on the surface everything is orderly, proper, and as it should be, but beneath the surface, the subconscious is raging with chaotic, antinomian, half-acknowledged desires. That is what Zweig gives us in “Eros Matutinus”—an official social attitude that rests upon suppressing the illicit desires whose existence it cannot admit.

Finally, this chapter should really always be read together with Arthur Schnitzler’s play La Ronde (available in English translations under titles like “Round Dance” or “Hands Around”). Schnitzler’s play, which could not be performed when first written, is a shocking exposure of exactly the widespread sexual hypocrisy that Zweig describes. Because it turns on a remarkably clever gimmick, I won’t spoil the play here with a description. (Who knows, maybe I’ll want to write about it later, and I can spoil it then!) It is breathtakingly provocative in its frank treatment of sex, but at the same time remarkably delicate and restrained, never resorting to explicit descriptions of the act itself—it is all but impossible to imagine one of our contemporaries treating sex with the same combination of boldness and restraint. Embedded within Schnitzler’s play is also quite a bit of social criticism—though you have to get past that initial reaction of shock, when you suddenly realize what he’s up to, in order to appreciate it.

I won’t say more about the play here, but there you go: along with chapter four of Zweig (“Universitas Vitae”), which we’ll discuss a week from now, I send you off with an extra recommendation. Just because that’s what we do here at FMB.

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you next time for another installment From My Bookshelf.

I'm almost tempted to read Zweig for the 3rd time! I have read Round Dance, but I missed the opportunity to read it alongside this chapter.

I'm curious if you've ever read John Irving? If you have, you'll know why I'm asking. (If not, I can tell you why!)

Max Ophüls made a marvelous film of 'La Ronde' in 1950.