I don’t think my family would have been very pleased with me had I spent Easter Sunday writing for Substack. But I did want to post something appropriate to the holiday, and the second day of Easter still counts, right? First, though, I am resharing a link to a piece I wrote last August entitled “The Voice That Speaks Through Many Voices.” In it I discussed the letter Pope Francis had issued on “The Role of Literature in Formation.” Francis, of course, died earlier today, so this is my small gesture in honor of his memory.

When Norwegian Jon Fosse won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2023, I had heard of his Septology but had never read any of his work. I’ve still never gotten around to Septology, I’m afraid, but I have read a couple of his shorter works, including, this past week, A Shining. This brief, 70-page novella by the Catholic Fosse turned out to be highly appropriate Easter reading.

Fosse is known for his spare, repetitive, stream-of-consciousness style, which may not be to everyone’s liking. Here are the opening lines from A Shining, as translated by Damion Searls (try reading them aloud):

I was taking a drive. It was nice. It felt good to be moving. I didn’t know where I was going, I was just driving. Boredom had taken hold of me—usually I was never bored but now I had fallen prey to it. I couldn’t think of anything I wanted to do. So I just did something. I got in my car and drove and when I got somewhere I could turn right or left I turned right, and at the next place I could turn right or left I turned left, and so on. I kept driving like that. Eventually I’d driven a long way up a forest road where the ruts gradually got so deep that I felt like the car was getting stuck. I just kept driving until the car got totally stuck.

For a hint of what Fosse is up to in this short book, compare those lines to the following, much better-known ones:

Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself within a forest dark,

For the straightforward pathway had been lost.That is of course the opening of Dante’s Divine Comedy (in the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow translation). And there is no doubt that Fosse, whose unnamed first-person narrator finds himself lost in a dark forest and unable to make his way out, wants us to hear the echo of Dante.

Fosse, whose A New Name (Septology VI-VII) was shortlisted for the 2022 International Booker Prize, named Dante’s great epic as an influence in an interview given to the Booker Prize Foundation. When asked to name “an older work or classic” to which he returned “time and time again,” Fosse answered: “Divina Commedia.” And Dante’s work reverberates throughout A Shining, not only in its opening pages. Not quite halfway through the book, for instance, the night darkness is brightened when the narrator looks up and sees the moon and stars:

And it’s dark, so dark and black that I can’t see anything, and it’s big, the forest is so big that I can’t find a way out of it, and it’s so dark and black that I can’t see anything, or, yes, look there, up there, the moon has come out, yes, and there it is in the sky, so round, so friendly, and there, yes, there are stars in the sky too, lots of stars, clear bright stars, twinkling stars. Yellow moonlight and twinkling stars. It’s beautiful.

It is hard not to be reminded here of the end of the Inferno, when Vergil and Dante leave Hell and return to the surface of the earth:

We mounted up, he first and I the second,

Till I beheld through a round aperture

Some of the beauteous things that Heaven doth bear;

Thence we came forth to rebehold the stars.There are other similarities between A Shining and its great predecessor. The lowest depths of Dante’s Hell turn out to consist not of burning flames but rather frozen ice; in Fosse’s forest, it begins to snow and grow cold. (“Because I’m freezing,” thinks the narrator. “Yes, I’m really freezing. I feel colder than I can ever remember feeling before.”) The protagonists of both books, experiencing an existential crisis, receive heaven-sent visitors who provide comfort and guidance. Both works have a clear three-part structure.

Yet Fosse’s work by no means maps neatly onto Dante’s, nor is the meaning of his allegory always clear; indeed, it becomes progressively less so as the book proceeds. This is most evident if we consider the three sections into which the novella falls. A reader anticipating a Hell-Purgatory-Paradise structure—as, I confess, I was after the opening—will be stymied. The three divisions of Fosse’s novella are framed not by different locations or obvious stages of spiritual progress, but rather by three visitations the narrator receives (more like A Christmas Carol, in that sense, though I doubt there is any intended parallel).

The narrator’s first encounter is simply with a mysterious shining presence: “A whiteness. It’s so clear in the black darkness. So shining white. A shining whiteness.” At first a mere outline, it becomes “a solid white shape” in the form of a person, though without any gender, “luminous in its whiteness” but not painful to look at. The speaker considers trying to touch it but immediately thinks doing so would be inappropriate: “You can’t just touch a whiteness like that. Because if you did you’d probably get it dirty. And imagine getting something so white dirty. No, how could I even think of doing something like that.” And suddenly, he realizes, “I didn’t feel cold anymore. I wasn’t freezing anymore, instead I felt a warmth coming at me from the presence.”

This “shining whiteness” is clearly divine—perhaps a person of the Trinity, perhaps simply the Godhead, but unmistakably divine. At one point, the narrator begins speaking to it, and it replies: “I’m here, I’m here always, I’m always here—which startles me, because this time there was no doubt that I’d heard a voice, and it was a thin and weak voice, and yet it’s like the voice had a kind of deep warm fullness in it, yes, it was almost, yes, as if there was something you might call love in the voice.” A few pages later, the narrator again addresses the shining apparition, asking it, “who are you.” The answer is telling: “The presence says: I am who I am—and I think that I’ve heard that answer before, but I can’t remember where I heard it, or maybe I read it somewhere or other.” He has heard it before, of course, in Exodus 3:14, when God addresses Moses from the burning bush with precisely the same words.

If the symbolism behind this first visitor is clear, however—perhaps even too heavy-handedly clear, as if Fosse were shaking us by the shoulders and shouting, “It’s God!”—that of the second and third encounters is far more perplexing. The narrator next meets a pair of people walking towards him through the forest. He is excited, hoping they might be able to show him the way out. As they draw nearer, he can see that it is an elderly couple, perhaps married, because they are walking hand in hand. When he addresses them, the old woman replies, “finally, we found you,” which he finds odd. But it turns out that he knows them well, for when he asks who they are, the woman replies, “can’t you tell from my voice, I’m your mother, don’t you recognize your own mother’s voice, unbelievable, not recognizing your own mother’s voice.”

As that nagging comment indicates, there is an element of humor in the parents’ appearance, playing upon some common stereotypes. The mother is talkative, the father distant and silent until she insists on a response from him. The mother chides the narrator occasionally—“why are you just standing there, don’t just stand there like that,” she says to him. Sometimes the parents’ dialogue sounds as though it could come from a comedy sketch:

[My mother] looks at my father and she says: say something, why are you just standing there not saying anything, can’t you talk, have you lost the use of speech, you need to say something—and my mother looks at my father and she says: say something, you too—and my father doesn’t say anything, and she says: it’s always the same, you never say anything, not even when your son is standing right in front of you just a few feet away do you say something, can’t you say something, you need to say something, you need to say that he has to come with us and then we have to get out of the forest, walk out of the forest together—and my father says yes. My mother says: you can’t just say yes—and my father says no, and my mother says: you just say yes or no—and my father says yes….

But what do these parents represent, and what are they doing here, following hard on the heels of the “shining” that gave itself the name of God? When the mother first identified herself and said, “I’m your mother,” my initial thought—still expecting the book to map onto the Divine Comedy—was that she might represent Mary. And to be sure, one can imagine a somewhat earthy, comic, “realistic” portrayal of Jesus’ parents along these lines, with a sharp-tongued Mary, perhaps chiding her son for having stayed behind in the temple and made them come searching for him, then turning on a hen-pecked Joseph, complaining about the mess he’s gotten them into, and demanding that he say something to their troublesome son.

But that does seem a bit irreverent for the Catholic Fosse, and it becomes a little hard to suppose that we are seeing an image of the Holy Family here. Perhaps it would be better simply to conclude that these parents have been sent in search of their son as guides to help him find his way out of the forest, much as Vergil or Beatrice—real human beings, both of them—sought to help Dante escape his own “forest dark.” Their significance remains somewhat ambiguous, however.

The narrator’s third encounter is even stranger. Like the “shining” before them, his parents disappear, and the moon comes out once more. He hears them again, again they vanish; once more he hears them discussing him and wonders where exactly they might be. Then suddenly he sees someone else:

But look, look over there, yes, over there between two trees, yes, there, yes, yes, there’s a man standing there. And he’s dressed in a black suit. And he’s wearing a white shirt. And a black tie. And he’s barefoot. He’s standing there barefoot in the snow. But that’s not possible.

Indeed, it doesn’t seem very possible, and this figure is surely the strangest thing in the entire book. A black suit, white shirt, and black tie? And barefoot? What to make of this?

That last detail, barefoot, seems perhaps most peculiar, but perhaps it can point us in a useful direction. For it seems to return us to the third chapter of Exodus once again. When Moses approaches the burning bush, God speaks to him out of it. “Take your sandals off your feet,” he tells him, “for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.” Our narrator, it seems, has reached holy ground.

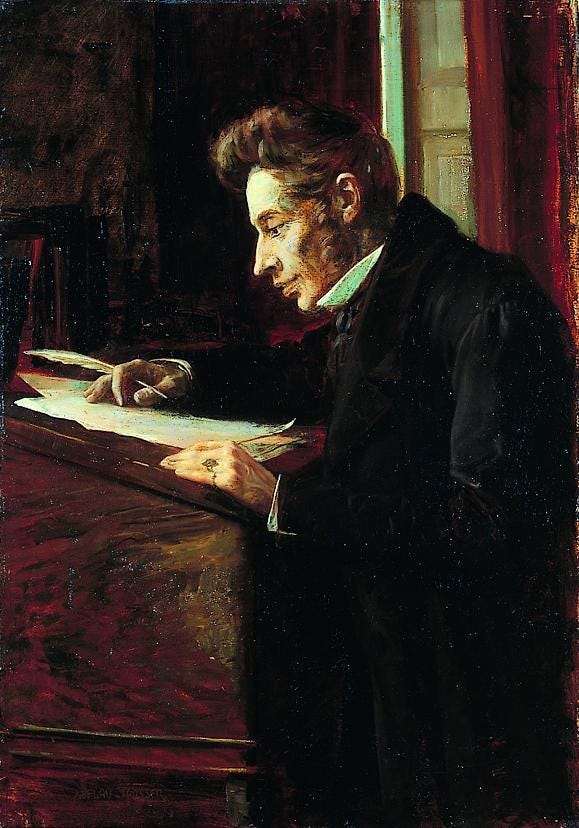

But what of this character’s strangely formal dress? Here let me venture what might initially seem an odd interpretation. If one does a bit of reading about Fosse online, one discovers that among the thinkers and writers most frequently cited as influences upon him is Søren Kierkegaard. Perhaps the most iconic image of Kierkegaard is a 1902 painting by Luplau Janssen entitled Søren Kierkegaard at His High Desk. And in this painting, Kierkegaard is dressed precisely as Fosse’s narrator describes this strange man he meets: black suit, white shirt, black tie.

But could this figure possibly be Kierkegaard? Interestingly, the text drops a strong hint that the answer could be “yes.” As the narrator watches the man in the black suit, the white shimmering presence appears beside him. This all seems so absurd to the narrator that he almost starts laughing, then catches himself.

But laughing when things are the way they are now, no, there are limits. But actually it doesn’t seem like there are any limits. Everything is sort of beyond the limits, it’s like being locked into a closed room in the forest, trapped, but at the same time it’s like the room is unbounded. It’s not possible. Either it’s like this or it’s like that. This way or that way, yes. Mother or Father. The white presence or the man in a black suit. Either I stay in the forest or I get out of the forest. Either or. And either my car will just stay stuck or I’ll get it unstuck. That’s how it is. Either or.

Either/Or, of course, is the title of one of Kierkegaard’s most famous works, and it is impossible to think we are not supposed to be reminded of this by Fosse’s repeated “either or.” Indeed, we might recall the beginning of A Shining, where the narrator says, “Boredom had taken hold of me.” And then we might also recall that Kierkegaard once wrote, “Boredom is the root of all evil”—I believe in none other than Either/Or, though I admit it is a text with which I am not very familiar.

As the book moves toward a conclusion, the man in black and the parents together approach the narrator, with the white shining presence nearby. “I see the man in the black suit walk over to my mother and he takes her free hand, and so my mother is standing there holding the man in the black suit with one hand and my father with the other hand, and now I see it, yes, that both my mother and father are standing barefoot in the snow there, they’re barefoot too.” But that is not all. The mother tells the narrator that he has to get up off the stone where he has sat down to rest, has to get up and come along:

I have to get up and come now, she says and I get up and I take a couple of short steps forward, and I look down, and I see that now I too am barefoot, and that’s strange, because I can’t remember taking my shoes off, but I’m barefoot now, that’s for sure.

So all of them—the man in the black suit, the parents, and the narrator—are all barefoot, standing, it would seem on holy ground.

Is it too much to imagine that Kierkegaard here has become the Vergil to our narrator’s Dante, leading him up to Paradise? The man in black takes the narrator’s hand too, and suddenly he is “inside the shimmering white light.” It is like fog, but also like “a kind of clarity, in a way.” Together, they all begin to walk out of the forest, hand in hand, becoming “part of the shimmering apparition.” And in the book’s closing lines, that shimmering presence addresses the narrator one more time, now quoting words of Jesus from the New Testament, as all becomes brightness and light:

[T]hen suddenly I’m inside a light so strong that it’s not a light and, no, it can’t be any light, it’s an emptiness, a void, and yes if it isn’t the radiant presence there in front of us, yes, the presence shimmering in its shimmering whiteness, and it says follow me, and so we follow it, slowly, step by step, breath by breath, the man in the black suit, without a face, my mother, my father, and I, we walk barefoot out into the void, breath by breath, and suddenly there’s not a single breath left but only the radiant, shimmering presence that lights up a breathing void, what we’re breathing now, with its whiteness.

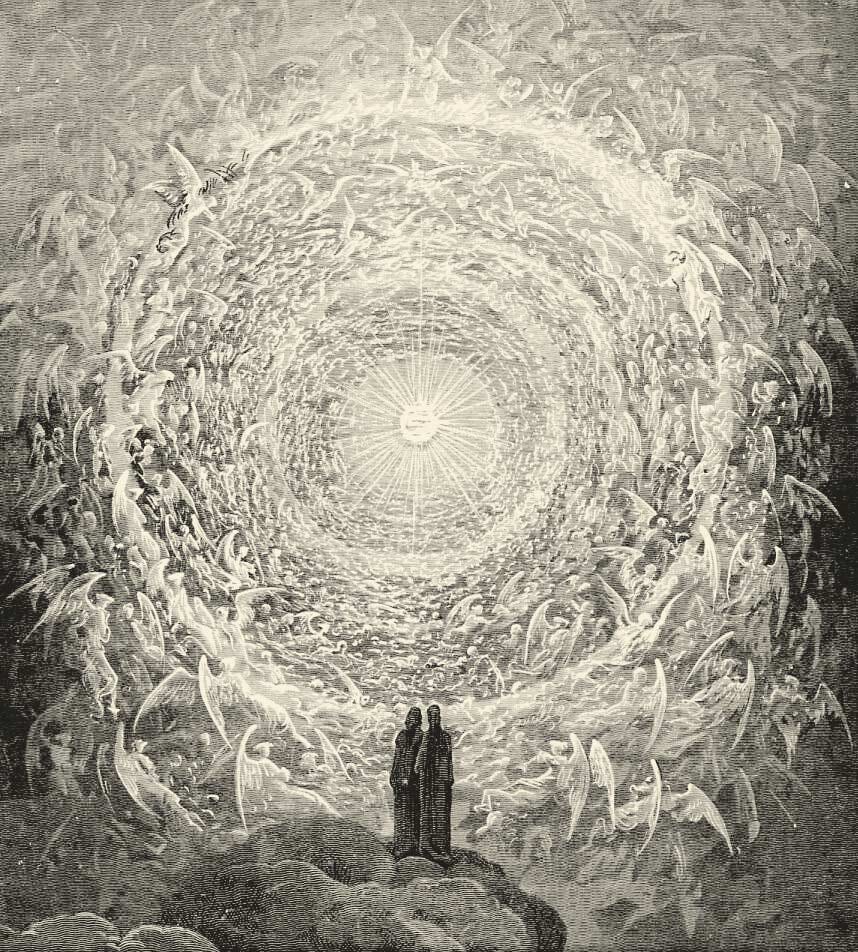

With that conclusion we return again to Dante, no longer to the beginning of the Inferno, but now to the end of the Paradiso, where Dante tries to give some faint image of the beatific vision he had been granted when contemplating the Trinity at the close of his journey. There too all was light:

Not because more than one unmingled semblance

Was in the living light on which I looked,

For it is always what it was before;

But through the sight, that fortified itself

In me by looking, one appearance only

To me was ever changing as I changed.

Within the deep and luminous subsistence

Of the High Light appeared to me three circles,

Of threefold colour and of one dimension....

O Light Eterne, sole in thyself that dwellest,

Sole knowest thyself, and, known unto thyself

And knowing, lovest and smilest on thyself!Like Dante, Fosse’s narrator has begun by going astray in the dark forest and has ended with a vision of radiant light. Fosse’s allegory is not always clear, and there are surely other ways to read it than the one I have sketched out here. But some of its important echoes—to Exodus 3, to the Divine Comedy, to Kierkegaard—seem evident enough. As does its general trajectory and thrust: that even in the 21st century, we can make our way from boredom, darkness, cold, and isolation into the bright light that calls to us, “Follow me.” Which makes this tiny little book a very appropriate selection for Easter.

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you next time for another installment From My Bookshelf.