On Friday, January 20, 2017, I was in London, having recently arrived for a semester teaching in Houghton’s honors program. That morning our group of about 20 students arrived from the States. My colleague and I met them at Heathrow, traveled with them back to the guest house where they would be staying, and got them checked in. Then, as is our custom, we prepared to take them on the “death march”: a roughly three-hour walk through central London, designed to give them their first experience of public transportation, show them a few of the most famous sights, and, most of all, help keep them awake until evening so that they would adjust quickly to the jet lag and be ready for their first class bright and early Monday morning.

But on January 20, 2017, there was a hitch that required us to adjust our usual route. That was the day of Donald Trump’s first inauguration as President of the United States. And thousands of Brits were gathered in central London for a march of their own, protesting the new American president. Streets were closed, not all of the usual transport connections would work, and we needed to be well clear of Trafalgar Square before the protestors descended upon it.

I was not a supporter of Trump, but I remember at the time thinking that there was something deeply ironic about this. As if the Brits didn’t have enough problems of their own! This was a mere seven months after the Brexit referendum; it was six months after Theresa May had become Prime Minister, a post she would fill neither very long nor very successfully; it seemed that every other day the headlines of the UK newspapers proclaimed calamitous problems with the NHS, the country’s national health service. Londoners had nothing better to worry about than a new American president?

That was then, this is now. I am back in London, teaching in the same honors program. This year my students arrived on Friday, January 17. We got them settled in and made sure they all had phone service but postponed the death march for a couple of days to allow your trusty scribe to recover from a nasty bout of flu or covid or something that has laid me low much of the past week. Thus in 2025, as in 2017, I found myself marching with a group of students through central London on January 20. And in 2025, as in 2017, January 20 was the day of Donald Trump’s inauguration as President of the United States. Take 2.

In 2025, however, we did not need to adjust our route. There was no large protest march. This may indicate Trump fatigue. Or the normalization of his brand of populist politics. Or perhaps that the UK’s own problems have only grown worse in the intervening years. None of which is a terribly encouraging possibility.

The discerning reader will have noticed that I have been in London for both of Trumps’s inaugurations. It may appear that I am fleeing the country. It only looks that way, really.

As for the UK’s own problems, I got my introduction to British politics this time within hours of our arrival. The driver who picked up my family and me at the airport, with our four months’ worth of luggage, was punctual, courteous, and affable. And also a man of decided opinions, albeit genially expressed and with a high degree of tolerance for the possibility of disagreement. In response to my query about the state of things in the sceptered isle, he responded, “What is it they say…? The ship has sunk.”

Rishi Sunak was blessedly gone from the PM’s office. He had been hapless. Boris Johnson, his predecessor, had been dragged out of some circus. Not to fear, I pointed out—now they had Keir Starmer at the helm. “Oh, yes,” he quickly replied, “that will take care of everything.” None of these gentlemen were really running the show anyway; they receive their marching orders from a vague coterie of ringleaders calling the shots—I wasn’t entirely clear who these puppet masters were, but I did not press the issue. The NHS is still a mess; his partner, a nurse, reported hospitals unable to keep up with the latest wave of influenza tearing through the capital. He had bought an electric vehicle for his business in part because of the exemption granted from various taxes and fees for driving in the city; now that exemption was about to be revoked. Clearly, the ship had sunk. He had not abandoned all hope, however. “You’ve just got to stay positive,” he assured me repeatedly, a refrain punctuating his various laments.

A few days later, feeling that as a visiting political scientist I should seek additional sources of information beyond my driver, pleasantly articulate though he had been. So I bought a copy of The Times of London. The lead story announced that Nigel Farage had moved within a point of Keir Starmer in the latest polls, while his Reform Party had overtaken the Tories for second place. For those who don’t know, Farage was a driving force behind Brexit, and he is now more or less the UK’s version of Trump. The very possibility that he could become prime minister, unlikely though that still seems, is astounding. Of course, other recent elections have also had surprising results.

Taking on a bit of water, that ship is.

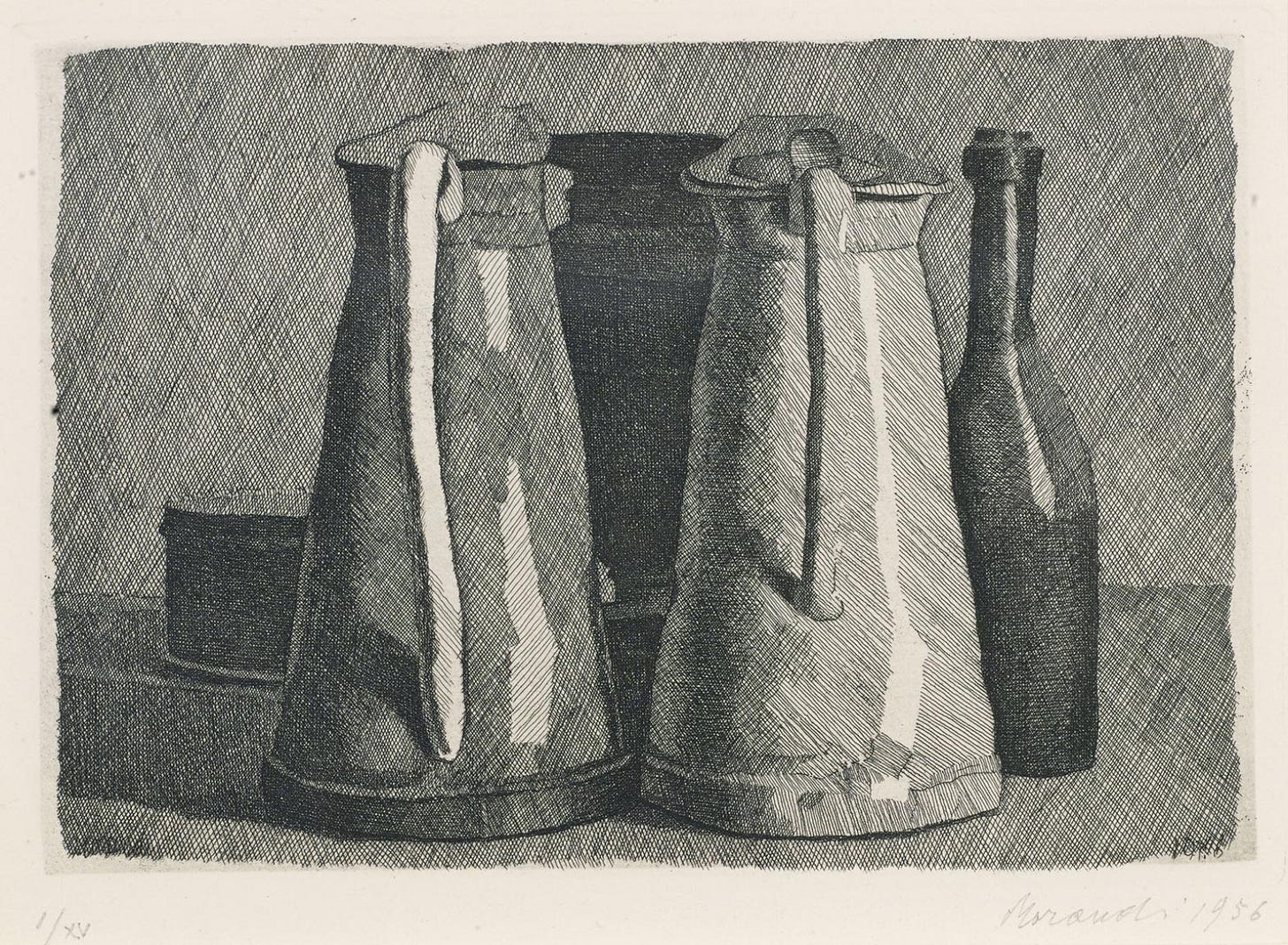

But all is not doom and gloom here in the fine city of London. You’ve got to stay positive, after all. Within a few days of arrival, I made my way back to one of my favorite small museums, the Estorick Collection, devoted to Italian modern art. They have some wonderful futurist paintings, such as Giacomo Balla’s The Hand of the Violinist or Luigi Russolo’s Music. Whenever I return, I am astounded anew by their room of Giorgio Morandi’s prints and etchings, which sometimes achieve remarkable levels of detail, light, and shadow, and at other times evoke the forms of still life with a bare minimum of outline.

I had another target in mind before leaving the Estorick. While teaching a seminar on Orwell’s journalism last fall, I had noticed the return address on many of his letters: 27b Canonbury Square. At the time, I thought to myself, “You know where that is.” So this time I stepped outside the Estorick, crossed Canonbury Square diagonally to the opposite corner, and there, sure enough, was one of London’s numerous plaques commemorating famous former residences, in this case a green one, erected by the local Canonbury Society: “George Orwell, Novelist & Essayist, lived here at 27b, 1944-1947.” Very neat.

I’ve been reading a bit, though less than I might like, what with welcoming students and falling ill. But one of my wife’s first missions when we are here in London is to procure library cards from our local branch, which this time is Highgate Library—the first public library in St. Pancras, as it happens, with funding originally provided by Andrew Carnegie. I tagged along as she and our daughters picked up their cards, and on the new arrivals table I spotted Baumgartner, by Paul Auster. I had seen this at a bookstore back home some months ago and briefly considered buying it based on the cover blurb: “The life of Sy Baumgartner—noted author and soon-to-be retired philosophy professor—has been defined by his deep, abiding love for his wife, Anna. Now Anna is gone, and Baumgartner is embarking on his seventies while trying to live with her absence.”

Not a must-read, perhaps, but faintly wistful and poignant, at least for another professor who loves philosophy, books, and his wife. While waiting on my family I began to read, and within the first ten pages Baumgartner had wandered downstairs to retrieve a book, only to be distracted by a pot he’d left simmering far too long in the kitchen; before he could clean up the mess from the pot, he was distracted again, this time by a phone call, not from the sister he expected might call to chide him for not having called her first, but rather to remind him that his meter reader was coming, a meter reader he couldn’t remember expecting; then the doorbell supplied another distraction, now from the UPS delivery woman bringing a book he’d ordered not because he expected to read it but for the sake of a visit from that very UPS woman, for whom he nourished a secret affection; and by time time all of this had happened, of course Baumgartner had long forgotten his original reason for coming downstairs.

I decided that anyone who could be so quickly, easily, and often distracted and who could so readily forget what he was doing was someone to whom I bore an uncomfortable similarity. So I checked out the book.

And have finished it over the course of various bus and subway trips. I’m not sure that the rest quite lived up to that charming beginning. But it was an enjoyable read, raising questions about how we deal with loss and how our memory reshapes our past. I wouldn’t necessarily recommend that you purchase Baumgartner. But if you come across it in the library, you won’t regret checking it out and devoting a few hours to it.

I am staring at the last drops of my latte, which I will take as a sign that I should wrap up this particular post. I don’t want to wear out my welcome here at Cinnamon Village, a nice little café on Blackstock Road in Islington, where the proprietress, delightfully, remembers me from my previous stays in London. When I walked in last week, she looked up and said, “So you’re back in London again?” Very nice to be in such an enormous, teeming city, and to have a few people who recognize you as if you were a local. Watch for future letters to hear about the National Gallery, or the Charles Dickens Museum, or the other reading I’ve started on—and, of course, updates on the condition of the ship.

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you next time for another installment From My Bookshelf.

Correction: My son has pointed out to me that Liz Truss, not Boris Johnson, was Rishi Sunak’s predecessor as British PM. I might try to excuse myself by pointing out that Truss’s tenure in office was so astonishingly short as to make Theresa May look like a British FDR. But, of course, he is entirely correct. Our children remind us of our shortcomings. Mea culpa.

Yes indeed, picking up on Mary von Nortwick;s mention of the proverbial Chinese curse regarding the inevitability of living in interesting times, I'm glad that you are enjoying the early unfolding of your latest teaching sojourn in London... and sincerely hope that on your return to the DUSA the books you make mention of have not been struck from library and bookshop shelves by one or other of the executive edicts that are being signed off with ever more frequent florid flourish by the Enlightened Hand of Trump the Most High.

Just me passing, satiric, comment based on what's striking and sticking with me.

Stay well Peter and know that London is not quite the whole story when it comes to what England, Northern Ireland (in which I include Eire), Scotland and Wales have to offer to the intellectually curious traveller 😊

Yes, the ships are sinking everywhere. I am reminded of that old Chinese curse: 'May you live in interesting times.'