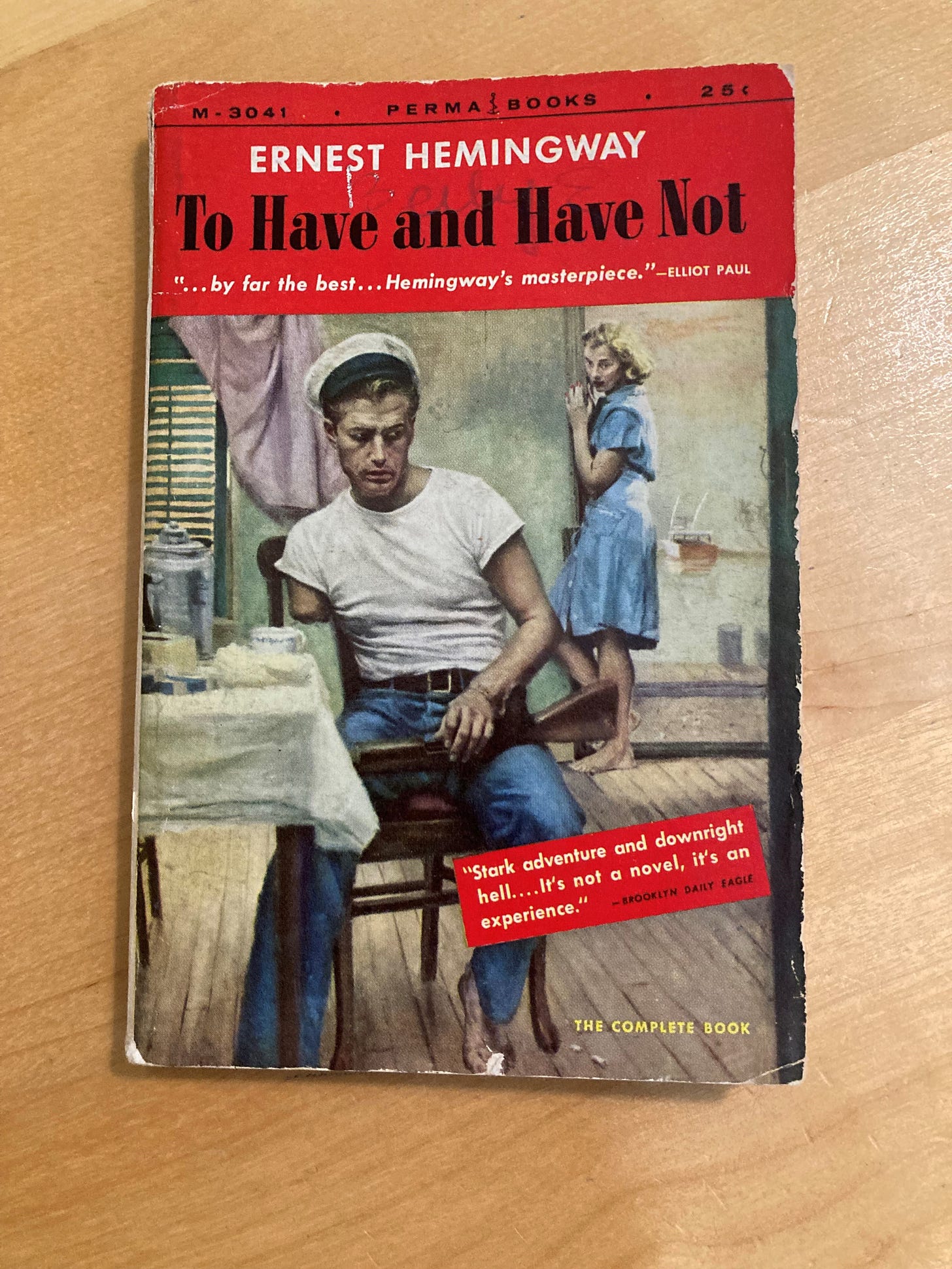

I did not realize it until the Library of America’s “Story of the Week” e-mail came through my inbox yesterday, but today is the 125th birthday of Ernest Hemingway, who was born on July 21, 1899. I figured I should mark the occasion by reading something by him, which I hadn’t done in many years. But what? Turning to the shelves at home, I saw a few familiar titles that were too long to plow through in what remained of the weekend. Oddly, there was no copy of The Old Man and the Sea, which might have been the obvious choice. But there was an old pulp-style paperback edition of To Have and Have Not, which I must have bought decades ago but had never read, sealed in a little plastic bag. The decision was made.

To Have and Have Not, published in 1937, is set mostly in Key West, Florida, where Hemingway himself lived for the better part of the 1930s. Consisting of three parts—a pair of stories that he had earlier published independently and a novella-like third section that he wrote later in order to create the novel—it tells of Harry Morgan, a down-on-his-luck fishing boat captain trying to scratch out a living by taking wealthy clients out on fishing trips in the Florida Keys or off the coast of nearby Cuba. As the novel begins, one of these clients secretly departs Havana without paying Morgan any of the money he owes him. Morgan is left penniless, without funds to pay for his return voyage or to support his wife and daughters if he does manage to get home.

Lacking any good options, he decides to accept an offer to smuggle a dozen Chinese men illegally to the Florida coast. But he double-crosses the men, first murdering the Chinese smuggler who has hired him—Morgan snaps the man’s neck with his bare hands—then dumping the migrants elsewhere on the Cuban shore before setting off himself for Key West. Though Morgan had accepted the job only reluctantly, he feels no particular remorse. He has only done what he had to do in a rough world. Hemingway captures his hard-boiled character in a lyrical comment that is abrupt and shocking after the act of brutal violence we have just witnessed. Opening his last remaining bottle of liquor and setting a course for home, Morgan thinks,

I tell you I felt pretty good steering, and it was a pretty night to cross. It had turned out a good trip all right, finally, even though it had looked plenty bad plenty of times.

Classic Hemingway, that.

In the book’s short second part, we learn that Morgan has taken to running bootlegged liquor illegally between Cuba and Key West. In the wake of an altercation, he is trying to get his badly damaged boat back to shore. He has been shot in the right arm, which dangles uselessly, and has to dump his illicit cargo overboard before he is discovered. He manages, barely, but not before arousing the suspicions of a government officer on a passing boat. “I hope they can fix that arm,” he says to himself as the section concludes. “I got a lot of use for that arm.”

In the third section, which accounts for over the half the novel, we learn that they could not fix that arm. Harry has lost it. As well as his boat, which has been confiscated by customs agents. So one-armed Harry Morgan—“hard, ruthless, implacable,” as the back cover of my old paperback describes him—desperate for income to support his family, resorts once again to smuggling people. This time it is a group of Cubans, political radicals who rob a bank at gunpoint in order to fund the revolution back home in Cuba. They dash directly from the bank into a boat Morgan has chartered for the purpose, and they take off for Cuba, seeking to get away before a chase can be organized. Morgan knows that they plan to kill him before landing, so it becomes a matter of who can get whom first. Outnumbered four to one, he boldly starts a surprise shootout, killing all four of his opponents… but also getting shot in the belly himself. Leaking gasoline from the gunfire, he shuts off the boat’s motors, letting it drift. A day later it is discovered and towed back home. Morgan is alive, though largely incoherent. He dies on the operating table, leaving a widow and orphaned daughters behind him.

In many respects, To Have and Have Not is really not a great book. The hard-boiled machismo is vastly overdone, with truculent, wisecracking tough guys getting in fights, often extremely violent or even murderous ones, for little or no reason. The dialogue can also get pretty awful, almost a kind of self-parody. Here’s a brief sample from Morgan’s conversation with a shady attorney who is arranging the rendezvous with the Cuban burglar-revolutionaries:

“I’ll be tied up to the dock there at the front of the street. It isn’t half a block.”

“All right.”

“That’s all.”

“All right, Big Shot.”

“Don’t you big shot me.”

“However you like.”

This sort of thing pops up on almost every other page and starts to feel a little embarrassing.

The novel’s third section is also much less tightly structured than the first two. In it, Hemingway introduces a subplot involving several wealthy residents of Key West, in particular a vain, dissolute writer named Richard Gordon and his attractive wife. Though the husband does not fully realize it, their marriage has been crumbling due to his own egotism and philandering. We see it finally collapse. Hemingway, who wrote this novel under the influence of Marxist ideology he had encountered during the Spanish Civil War, clearly wants to emphasize the contrast between economic classes, the “haves” and “have nots” of the book’s title. A man like Harry Morgan is willing to work hard and takes risks in order to provide for his wife and daughters, but he is driven to crime and finally a meaningless death. Meanwhile, someone like Gordon lives it up, vacationing to Key West, having repeated affairs, all the while ignoring his own wife. (Obviously, our Cuban bank robbers, one of whom gives Morgan a short pep talk on the virtues of the revolution, also provide Hemingway an opportunity to introduce the rhetoric of class struggle, though they are hardly sympathetic characters.)

But these episodes, including a late chapter where an omniscient narrator provides glimpses into several other yachts in the harbor and the lives of their wealthy inhabitants, feel relatively extraneous. Hemingway does not integrate them successfully into the narrative, and we do not get to know these characters the way we get to know Harry Morgan. Had they been omitted, the resulting novel, about 50 pages shorter, would have been more taut and compelling. Indeed, by keeping our attention more squarely focused on the so-called “Conchs,” the have-not natives of Key West, it would have awakened our sympathy for them more effectively.

Still, one doesn’t want to write about Hemingway on his 125th birthday and only be critical. So let me close by noting two of the book’s strengths. One is the character of Harry Morgan himself. He is no doubt a bit too much the stereotypical tough guy. But he is also brave, determined, and resourceful. His desire to support his family has a certain nobility. He does the best he can in a world rigged against him. His final, semi-coherent sentences shortly before his death express this. “A man,” he says. “One man alone ain’t got. No man alone now…. No matter how a man alone ain’t got no bloody f—ing chance.” (Pardon my—Hemingway’s—French.) About this, the narrator comments, “It had taken him a long time to get it out and it had taken him all of his life to learn it.”

The other strength, surprisingly, is Morgan’s wife Marie, whom we see for only brief segments of the narrative. Though Morgan says she is beautiful, another character describes her in much less flattering terms. She is past her prime. It is implied that she had worked as a prostitute before falling for Morgan, whom she clearly loves. She helps him prepare for his final voyage quickly and competently; though worried about what he might be doing, she does not ask too many questions. But she comes into her own in the book’s short closing chapter. It is a week after Morgan’s death, and she remains devastated. “I’ve got to get started on something,” she thinks. “Maybe you get over being dead inside. I guess it don’t make any difference. I got to start to do something anyway.” But she knows it will be hard to find anything. She reminisces about happy times together with Harry and wonders how she will continue without him.

How do you get through nights if you can’t sleep? I guess you find out like you find out how it feels to lose your husband. I guess you find out all right. I guess you find out everything in this goddamned life. I guess you do all right. I guess I’m probably finding out right now. You just go dead inside and everything is easy.

In the end, it is Marie, even more than Harry, who most powerfully makes us feel the plight of Hemingway’s have-nots. As the book ends, the world around her remains indifferent to her inner suffering: “Through the window you could see the sea looking hard and new and blue in the winter light.”

Happy Birthday, Ernest Hemingway.

Thanks for reading. I’ll see you later this week for another installment From My Bookshelf.

This is a good summary of the book. I love Hemingway, and I think this is his worst book. Even so, there were good parts in it. I agree with you that the ideological element weakens the book. He’s not really an ideological thinker or writer, he’s interested in individual human character. That’s what he’s good at.

I am so pleased to encounter your Substack and look forward to reading your insights. In my Comp. II class, I teach “Hills Like White Elephants,” and it leads to one of the most intriguing class discussions of the semester. Beyond introducing students to Hemingway’s distinctive stylistic characteristics & links to Modernism, we read part of the story as a type of one-act play as we consider the limitations of this relationship and the reasons for the projected failure of it by the narrative’s quietly wrenching conclusion—often through the framing device of I Corinthians 13. The students are typically very perceptive in noting that this poignant narrative provides a striking counterpoint to the shallow depictions of transactional & compartmentalized romantic relationships bombarding us in our modern socio-cultural environment. Thanks for your illuminating perspectives!