Not long ago, a question was circulating on Substack Notes asking people to name ten authors by whom they’d read at least five books. Soon afterwards someone upped the ante: name ten authors by whom you’ve read at least ten books.

It’s not actually so easy to read ten books by the same author. First, the author has to be fairly prolific; then, you either need to admire his or work over a very extended period of time or have a burst of quite intensive reading to hit that ten-book mark.

When I saw the question, though, I immediately knew a handful of authors who made my “ten book club.” And one of them would be 150 years old today: Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Burroughs (1875-1950) is not exactly in the first rank of literary figures; indeed, he was more or less a writer of pulp fiction. But he wrote a ton—more, perhaps, than he should have—and was immensely popular as an author of science fiction and adventure tales. In my early teen years, I devoured lots of them. I read only a few of the many novels about his best-known creation, Tarzan. But he also wrote a short series of novels set on Venus, and another in “Pellucidar,” a world at the “earth’s core”; I read most of both series.

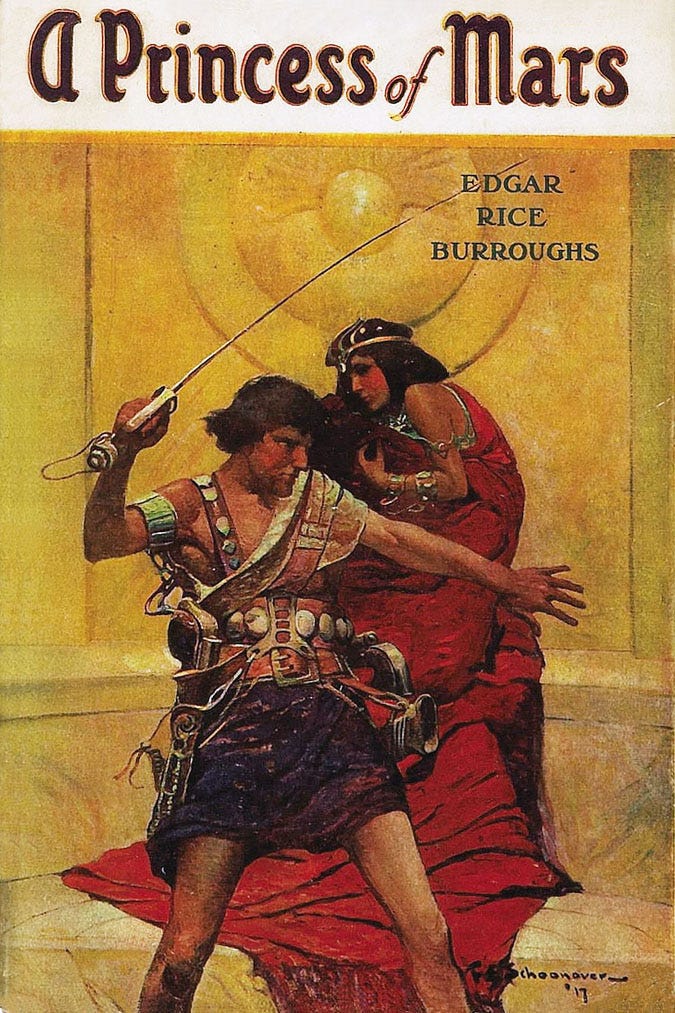

What I loved most of all, however—reading the full set of eleven novels—was his Martian series, set on the red planet called by its inhabitants “Barsoom.” So when I realized over the weekend that September 1 would be ERB’s 150th birthday, I knew exactly what book to reach for: A Princess of Mars, the first of the Barsoom novels, originally published in 1912 as Burroughs frantically sought to stave off financial ruin.

A Princess of Mars features the debut of John Carter, the series hero, a Virginia gentleman and former Confederate officer who heads to the Southwest after the war in order to prospect for gold. There he is chased by a band of Apache warriors into a cave, where a mysterious gas first makes him drowsy, then immobilizes him. Suddenly, he finds himself outside his own body, gazing down at it lying on the ground. Unsure whether he is dead or alive, he steps outside the cave, looks into the night sky, sees Mars floating above him, feels it “call[ing] across the unthinkable void”—and then, after a brief “instant of extreme cold and utter darkness,” awakens to find himself on Mars.

What follows is a rollicking, swashbuckling adventure tale that combines elements of science fiction, Western, and romance. Carter discovers that in the light gravity of Mars, he can leap great distances and possesses unusual strength and agility; already a fighting man by training, on Mars he is a kind of proto-superhero. Carter is not only strong, he also has all the best (and perhaps also the worst) qualities of the Southern gentleman: he is impulsive, with a powerful sense of honor, and intensely loyal.

He immediately finds himself taken captive by the Tharks, the green men of Mars, a race of enormous warriors, fifteen feet tall and with six limbs. The Tharks seem modeled on Sparta: they breed carefully, have no private families, raise their children collectively, and train exclusively for warfare. Though a prisoner, Carter wins their grudging respect—in particular that of Tars Tarkas, a leading captain—when his fighting prowess enables him to kill a pair of their chieftains.

But the Tharks are not the only inhabitants of Mars. One day a fleet of airships floats overhead, on a mission from Helium, capital city of the red men of Mars, the Martian race most similar to earthly human beings. The ships come under fire from the Tharks, suffering severe damage. One of them is carrying a precious cargo indeed: the princess of Helium, Dejah Thoris, granddaughter of Tardos Mars, the Jeddak—ruler—of Helium.

John Carter quickly falls in love with the beautiful, proud, brave, high-spirited, noble Dejah Thoris—the “incomparable” Dejah Thoris, as he invariably refers to her. The rest of the novel is one adventure after another as he strives to rescue her and return her to her people. Along the way we encounter the terrible, savage white apes of Barsoom; the Warhoons, a separate tribe of green Martians, even more ferocious than the Tharks; and the Zodangans, a second kingdom of red Martians at war with Helium. John Carter learns to fly the nimble Martin airships, goes undercover in the Zodangan palace guard as he searches for Dejah Thoris, and even stumbles upon the secret atmospheric factory that sustains the dying planet by producing breathable air from the “ninth ray” in sunlight, unknown on earth but discovered by Martian scientists (like the eighth ray, which propels their aircraft).

We also meet other noteworthy characters, such as Sola, the Thark woman in charge of John Carter, unusual for her compassion, the product of her upbringing: the child of an illicit marriage, she, alone among the Tharks, knew her own mother, as well as the identity of her father, who proves none other than Tars Tarkas. Tars Tarkas himself becomes one of John Carter’s crucial friends and allies; as the book nears its conclusion, the two of them jointly lead a Thark attack to break the Zodangan siege of Helium, forging an unprecedented alliance between the red and the Green Martians. Carter finds another ally in Kantos Kan, a red Martian also briefly taken prisoner by the Warhoons. And then there is Woola, the Martian version of a watchdog who is set to guard Carter but becomes his own faithful companion when treated with human kindness rather than Tharkian severity.

A Princess of Mars is a novel of action and excitement, not one of ideas. And it is, frankly, a rip-roaring good tale. The action never flags, as Burroughs leads Carter through one close call and narrow escape after another. He serves up a healthy dose of Robin Hood-style swordplay as we root for our hero to defeat the bad guys, advance the cause of decency and humanity (Martianity?) over aggression and brute force, win the heart and hand of his lady-love, and even, eventually, rescue the planet Mars itself. The stakes could not be higher; John Carter barely has time to catch his breath, and neither do we. And of course all the while we have the pleasure of cheering on one of our fellow human beings as he becomes an interplanetary hero.

Burroughs has fallen somewhat out of fashion these days because of his racial views. He evidently endorsed (pseudo-)scientifically-grounded racism and eugenics. I don’t remember ever being struck by that in my youthful reading, and I really don’t know enough about any of his non-fictional writing to have an informed opinion about that aspect of his work. Lots of people in the early twentieth century did hold such views; it would not be terribly surprising if Burroughs shared them.

I will say, however, that I don’t see a bit of it in A Princess of Mars. Barsoom is divided among distinct races, to be sure. But not only do the color schemes not match a standard racist schema—the noblest Martians, after all, those of Helium, are red—the story also challenges racist assumptions. The red Martians are in fact a hybrid descended from earlier white, black, and yellow races. Tars Tarkas demonstrates that the fierce green Martians have potentially noble qualities. The red Zodangas are among the novel’s villains. One of John Carter’s greatest achievements is to forge the alliance between green and red Martians; Dejah Thoris says to him, “You have done in a few short months what in all the past ages of Barsoom no man has ever done: joined together the wild hordes of the sea bottoms and brought them to fight as allies of a red Martian people.” Carter himself marries a woman of another race, and when the book ends he and Dejah Thoris are expecting a child, waiting—in Martian fashion—for their egg to hatch after its five-year incubation period.

It is a mistake, I think, to read too much into A Princess of Mars. Burroughs was an aspiring writer; he was badly in need of money; he tried to write an exciting story that readers would enjoy. He succeeded.

I, for one, was happy to return to Barsoom and re-read this story I enjoyed long ago, and I found no reason to feel guilty about enjoying it again now Sometimes when we revisit a favorite book from our childhood, we discover to our disappointment that it doesn’t quite live up to our recollection of it. But A Princess of Mars had me eagerly turn the pages this weekend just as it did forty years ago. Clearly, Burroughs was doing something right.

As always, thanks for reading, and I’ll see you next time for another installment From My Bookshelf.