Each Sunday in Advent I’m bringing you a segment of Peter Rosegger’s short story, “Der erste Christbaum in der Waldheimat,” translated here into English for the first time (as far as I’m aware). “Waldheimat” was the name Rosegger invented for the region of Styria from which he came; after he rose to fame as an author, it became widely adopted as a label for the area.

Last week, in Part 1 (which you can find here), the story’s young narrator—in reality Rosegger himself, who included this story in memoirs of his youth—returned home for his first Christmas holiday since leaving for his studies. He received a warm welcome from his mother; his younger brother, Little Nicky, observed the newcomer carefully but shyly. The narrator, flushed from his climb up the mountain, laughingly points out that despite coming from the city, he has more color in his cheeks than Nicky does.

Little Nicky looked pale. “You’re the one with the city color, not me!” I said, and I laughed.

This is how it was. The little fellow kept coughing, half the winter long already. And there was an old housemaid who used to say, at least three times a day—I remembered it well from earlier—that nothing was worse for a “coughing lad” than “the cold air.” She forbade the little one to go outside in front of the door, she always kept the windows shut tight; even the door was only permitted to open just far enough and just long enough for a person to slip quickly in or out. Our parents were grateful to the old woman for helping take care of the child so conscientiously. As a result, the boy never got outside and never even caught a breath of fresh air in the parlor. I think that’s the reason he was so pale, not because of his cough. When I was a little boy, I used to cough too. But back then this old maid wasn’t around yet, and I romped around outside far and wide, together with my siblings; I threw snowballs, went sledding down the mountainsides, skidded around on the ice until my pants wore through, all of it for so long that the cough took care of itself.

But poor Little Nicky didn’t have any more like-minded comrades—among all the grown-ups, he was the only child, the poor little thing of the household, and he submitted helplessly to its rules. I diligently took advantage of my few days of vacation to turn him against the housemaid’s life-threatening ministrations. I lured him out of the house, so that his hands grew warm and his cheeks red. And by the evening he was coughing even more. My dignity as a gentleman from the city protected me against the worst, but the old woman couldn’t keep her opinion to herself: I ought to have remained there in what she called my pile of stones, instead of coming here in order to ruin children. Meanwhile, we went right on cheerfully enjoying our winter pleasures, and even before I returned to the city, my little brother’s cough had vanished.

But I’m getting ahead of myself, letting the time hurry along. And I really want to linger a while over the dear Christmas celebration.

In the night preceding it, I slept little—something unusual in those years. Mother had prepared a bed for me on top of the stove, with the warning not to stretch my legs out too far lest they end up in the fire pit, where the coals were glowing. Those smoldering coals were snugly comfortable; they crackled so nicely in the quiet darkness of the night and sometimes cast a faint gleam from the embers upon the wall, where the brightly colored bowls leaned against their frame. But the cockroaches! Every night they came creeping out of their holes in the walls and from time to time went for little outings across the limbs and face of a certain sleeping student! A healthy young boy, however, gets used to the cockroaches—even if they don’t get used to him.

On this particular night, however, it was a different matter altogether about which our student needed to make up his mind before mother stepped to the oven to cook our morning porridge. I’d heard quite a bit of talk about how they celebrated Christmas in the cities. There they would take a tiny spruce tree—a real little tree from the forest!—stand it up on the table, fasten small candles on its branches, light them, even place presents beneath it for the children, and then say that the Christ child had brought it. I had even seen pictures of Christmas trees like this. And now I intended to set up a Christmas tree for my little brother Nicky. Completely in secret, it goes without saying.

As soon as the daylight appeared, I ventured out into the frosty mist. This same fog protected me from the glances of people working around the house when I returned from the forest carrying the little pointed top of a spruce. I hurried with it to the shed where we kept our coach. There I drilled a hole in a piece of wood, inserted the little tree into it, and hid it under the wheels and axles. Then I headed over to the shopkeeper at Sankt Kathrein in order to buy apples. But he didn’t have any—that year’s crop had failed in Pöllau and Hartberg, so the fruit dealers hadn’t come up into the mountain region.

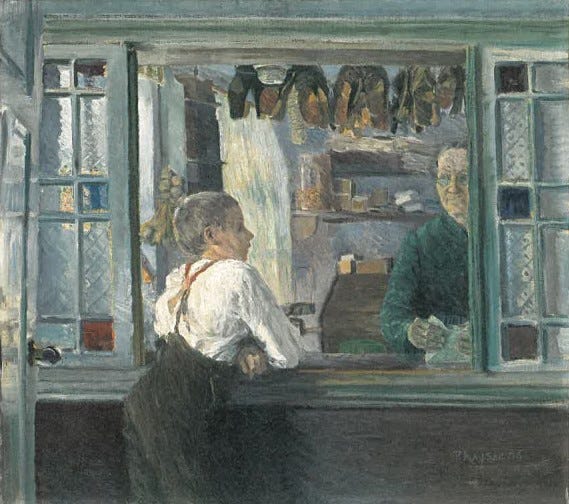

So then I asked the shopkeeper if perhaps he had some nuts.

“Nuts!” said he. “For cracking, or for looking at? I’ve still got one bag of them, left over from last year. But they’re only for decoration. If you crack them, you’ll just find a blackened or dried up kernel inside, and it won’t be any good for eating.”

I let him keep his nuts. I wouldn’t do a thing like that to my little brother: give him a pretty shell, with no nut inside. One mustn’t let a child get accustomed to tricks like that.

But then what was I to buy? He had all kinds of pretty things, that shopkeeper. Red handkerchiefs, suspenders, hand mirrors, pipes, even harmonicas. But even apart from the fact that our prospective educator found many of the items unsuitable, I had to reckon with my limited capital, which was still supposed to get me back to Graz again.

“Well then, I guess I’ve made the trip in vain,” I said.

To which the shopkeeper replied, “I’d hate for you to have done that, young man—if I may still address you that way, Mr. Student—so at least have a little drink.” And with that, he filled a tiny shot glass for me from a bottle of sweet, red schnapps.

After I had drunk it, my courage began to rise and my financial worries to diminish. But I didn’t buy anything at the shopkeeper’s—good old Haselgraber hadn’t made me a present of the wine with that in mind. I crossed the little bridge to the baker and bought a sweet roll for four kreuzers, sticking it carefully in my breast pocket, so that the wagon-driver Blasel, who then crossed my path, laughed and called out to me, “Lookie there, little Peter from the forest farm thinks he’s grown a man’s chest!”—for back then, the sweet rolls you got for four kreuzers at St. Kathrein weren’t of a size that you could keep hidden under your buttoned-up jacket.

I arrived at home, and now I had gathered everything for the Christmas tree….

I’ll be back next Sunday with Part Three, and we’ll find out if Peter manages to surprise his little brother with the Christmas tree! (And here was Part One, from last week.) Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you next time for another installment From My Bookshelf.

Subscriptions to From My Bookshelf are free for now, but you can support my work with a one-time donation. No donation is too small—and none is too large!