Walk into pretty much any used bookstore or old local library here in western New York, and you’re likely to run across a few volumes by Arch Merrill, the so-called Poet Laureate of Upstate New York. The prolific Merrill died in 1974, when I was not much more than a toddler, and long before I ever moved to the region. But he was a local legend, whose journalistic career led him to the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, where he spent about two and a half decades before retiring. (The Democrat and Chronicle is not much of a paper today, sad to say; one presumes it was better in Merrill’s day.)

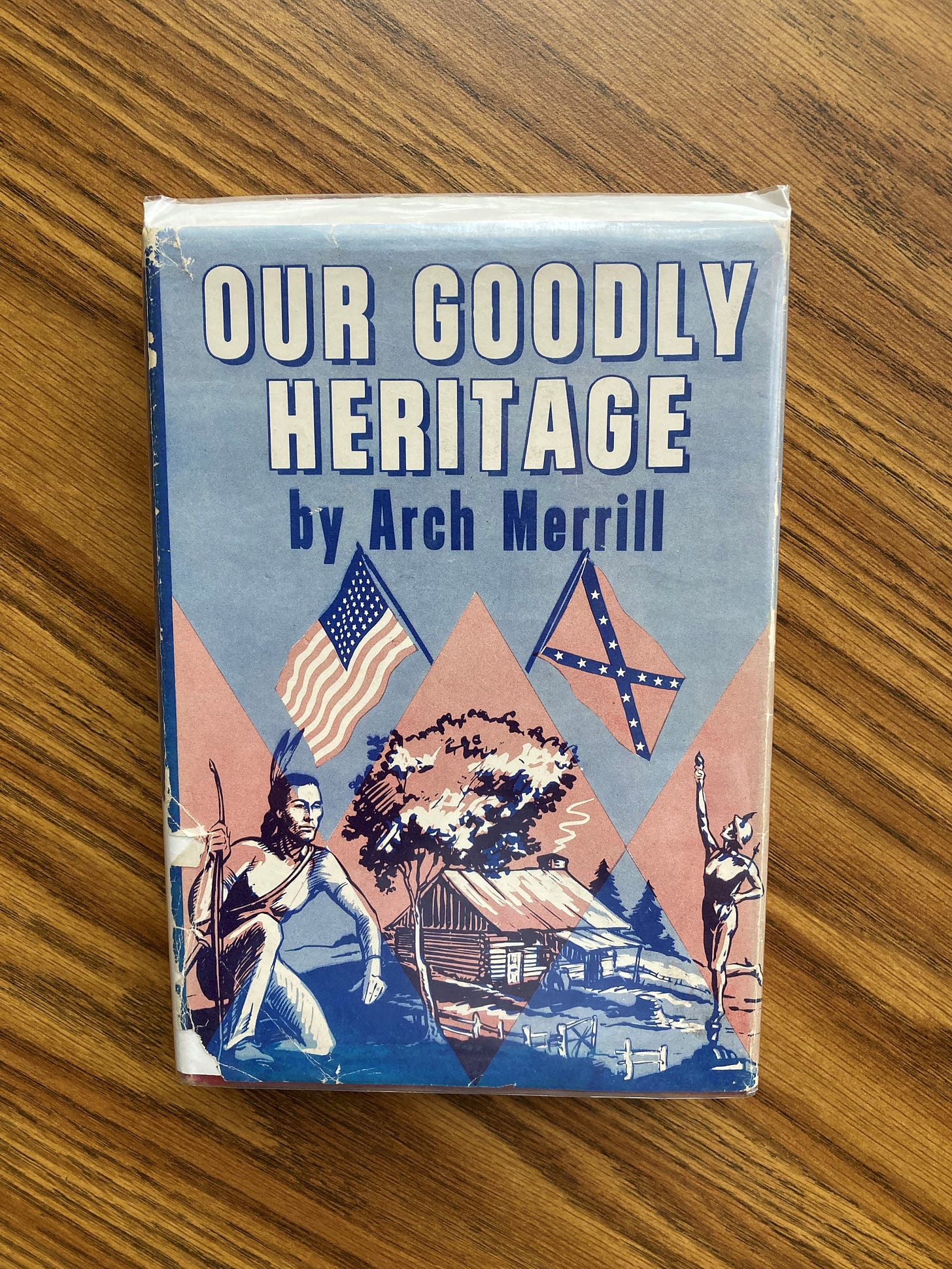

During that time he wrote a regular column about Rochester and its surroundings in upstate and western New York, producing, if Wikipedia is to be believed, a rather impressive 1,650 stories. Many of these were collected in a string of about 20 books. One of which, Our Goodly Heritage, is lying on the table before me.

Readers from elsewhere would not share my sense of recognition but can surely imagine the pleasure of reading about familiar places—prompting reactions such as “I’ve been there,” or “Do you remember when we saw that?,” or “We missed that last time—I guess we’ll have to go back and look again.” That’s the experience a western New Yorker has when reading Merrill’s columns, which combine regional history, journalism, folklore, legend, human interest, and local patriotism. They’re the work of someone determined to remind his readers that they don’t need to travel far afield in search of interesting people and places, because their own hometowns are already full of memorable stories, if they know where to look—or have the right guide.

Merrill recounts a tall tale, for example—an “elegant legend,” he calls it—about the town of Fillmore, about a five-minute drive to the north of me. It’s home to the local public school; our public library is in Fillmore; with my family, I attend church there every Sunday. Merrill claims to have heard this story from a barber named Sam, who told it to him while cutting his hair. I’ll go ahead and relate the whole story:

Around the time of the first World War [Sam] was working in the Northern Allegany County village of Fillmore. Living in the Genesee River town was a young section hand known to all as Patsy. Patsy had in his heart the music of his native Italy. He had a clear, sweet voice and he could play the mandolin.

Sometimes at night, after he had looked long upon the wine when it was red, Patsy would take his mandolin and climb out on the 155-foot-high viaduct of the Erie Railroad cutoff which straddles the valley east of the village.

The people who lived nearby would hear the music of his voice and mandolin wafted down from the high bridge. They speculated each evening after the chores were done whether Patsy would come to the bridge that night. When they did not hear his serenade, they were disappointed.

One night when the harvest moon was shining and all was still, Patsy’s song ended sharply—in the middle of a note. The neighbors did not think anything of it at the time. They figured maybe Patsy had dozed off.

The next morning they found his crushed body at the foot of the high bridge. His fingers still clutched the strings of his mandolin.

And ever since on moonlit nights in the harvest time, if you listen closely, you can hear elfin music floating down from the high bridge—Patsy singing as he strums his mandolin.

That’s the way Sam the barber told me the story. He told it as Gospel truth. In those days I did not recognize a legend when I heard one. So in my blindness I checked up on the story down Fillmore way. I found nobody who had ever heard of Patsy or his untimely end, to say nothing of hearing his real or spectral music.

I have to admit that I’ve never heard Patsy’s music either, though maybe I’m just a bit too far down the valley for his tunes to waft my way. I do know where the bridge would have been, however (it no longer exists), just off the road we used to take when our old cat had to go to the vet. Like Merrill, I admire Sam the barber’s creative talent in crafting “The Legend of the Minstrel on the High Bridge.” Perhaps the noises we sometimes take for the nighttime barking of foxes or hooting of screech owls are really the faint sounds of Patsy’s mandolin.

Merrill also probes the history of the area in interesting ways, sometimes describing well-known characters, but often memorializing ordinary people who would otherwise go unremembered. One of the latter caught my attention because, as with the legend of Patsy, I know the spot he is describing, Hope Cemetery in Perry, NY. For the past decade we’ve driven to Perry, 30 minutes north of here, several times a week, because our children took dance classes there. More times than I care to count, I’ve dropped them off and decamped a few blocks up the road to the public library in order to grade papers and prepare classes while they were practicing pliés, relevés, tendus, and the like.

Just a couple blocks more gets you to Hope Cemetery. In an essay describing touching epitaphs he’d discovered in various western New York cemeteries, Merrill reports coming across that of one Rufus Sweet in Perry:

Here lies Rufus Sweet and wife

That fed the hungry and clothed the naked

And fought secret societies

And here may they rest until

Gabriel blows his horn.

One would love to know more about those secret societies that Rufus fought with his wife! This epitaph caught my attention especially—not only because I read it just one day after I had bought Our Goodly Heritage at a used bookstore right there in Perry, but also because on that very same day, before starting to read the book, I had myself wandered into Hope Cemetery, taking advantage of some lovely fall weather to squeeze in a walk before settling down to work at the library.

I did not spot Rufus Sweet’s gravestone, though I’m tempted to return and search for it. But another tombstone caught my eye, right at the front edge of the cemetery, not ten yards from Main Street. I spotted it first for the impressive name: Le Grand D. Rood. I assure you, there are not a lot of young men roaming western New York these days who answer to “Le Grand.” But Le Grand’s name was not the only interesting thing about him. He died on June 7, 1864, at the age of 21 years, in Andersonville, Georgia.

Le Grand D. Rood must have died in the service of his country as a prisoner of war at the notorious Confederate prison camp in Andersonville. Indeed, his gravestone identifies him as belonging to the “24. Ind. Bat. N.Y. Vol.” Some internet searching suggests that this was the 24th Independent Battery of the New York Light Artillery, and I managed to find this short account of Le Grand:

ROOD, Le Grand D. - Corporal. Born at Elmira, NY, son of Simeon & Lydia A. Rood. Enlisted 28 Aug 62 at Perry, Wyoming Co., NY, a 19 year old Farmer. Mustered in 30 Aug 62 as a Private. Promoted to Corporal. Captured 20 April 64 at Plymouth, NC. POW at Andersonville, GA. (Squad 39, 3rd Mess) Admitted 4 June 64 to the prison hospital with Pleuritis. Died 7 or 8 June 1864 of Pneumonia at Andersonville, GA. Grave 1735. The morning the boys left for the front he called on Pembroke Safford at his home. The two had been inseparable thru life - had played together as children and attended school together. As Pembroke came out of the house he stepped over to the well and remarked, "I'll never see this place again." Both were captured at Plymouth and taken to Andersonville. Rood died on June 7, 1864 and Safford on June 12. Memorial Headstone in Hope Cemetery, Perry, NY. C. M. Norton, 1st MI Cavalry, a hospital assistant, states his death as 10 June 1864.

That sparse paragraph contains the makings of another “elegant legend,” I think. Le Grand’s epitaph is less informative than that of Rufus Sweet, but it poignantly combines words of comfort with sorrow at the death of a young man far from home:

Asleep in Jesus! far from thee

Thy kindred and their graves may be.

If Arch Merrill, the poet laureate of upstate New York, had come across the grave of Le Grand D. Rood, I imagine he might have preserved his memory for us along with those of Patsy the minstrel and Rufus Sweet, scourge of secret societies.

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you next time for another installment From My Bookshelf.

This also recalls for me your Walter Scott excerpt - and the legends and pull of place. Barber Sam might have been a closet writer making a living where he could. :-)

I grew up with Pacific NW writers on the shelves from this era, similar style of books. Are you familiar with the Rivers of America series, edited by Constance Lindsay Skinner? There’s a volume on the Genesee (and the Erie, Hudson, Delaware, Susquehanna…. And plenty more). Each one gathers folklore from the watershed. Impressive series.