The surprising thing was that so many people stayed at all.

Walter Edmonds and the American Revolution in Central New York

Some quick housekeeping notes before we get started:

First, thanks to all my subscribers. This weekend marked two months of From My Bookshelf, and your numbers are slowly growing. I’m grateful for your support. If you enjoy what you’re reading, please recommend it to your friends.

Second, I will almost certainly skip a post and take the rest of the week off. By the time you see this on Monday morning, I should be on the road to Denver, helping one of my daughters move across the country. I don’t expect to have time for reading, much less writing. I’ll be back again next week.

A little over a month ago, I wrote here about The Matchlock Gun, a children’s book by Walter D. Edmonds. At the time, I mentioned that I was reading a much longer book by Edmonds. I’ve been progressing in fits and starts, but I finally made it (telling myself that I absolutely had to get it done before taking off for Denver!).

I don’t know whether others’ educational experience matches my own, but in learning about American history, I don’t remember the American Revolution being described as a particularly violent war. We all hear of the horrors of World War II; probably many of us have seen gruesome images of Vietnam; no doubt most still learn at some point that the Civil War cost more American lives than any of our other wars. But the American Revolution? It’s mostly a blur of patriotic images: The Spirit of ‘76, Washington crossing the Delaware, Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown.

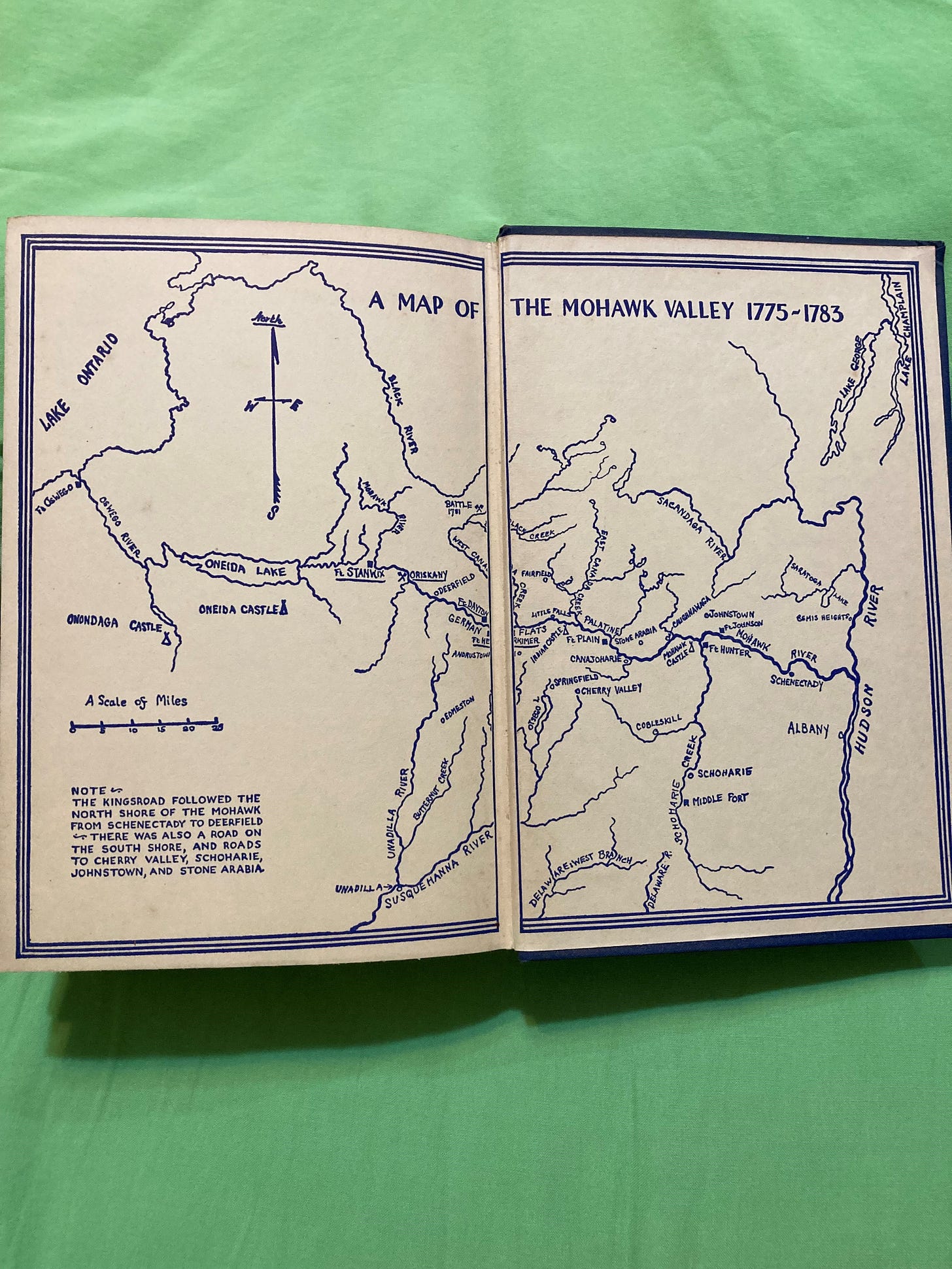

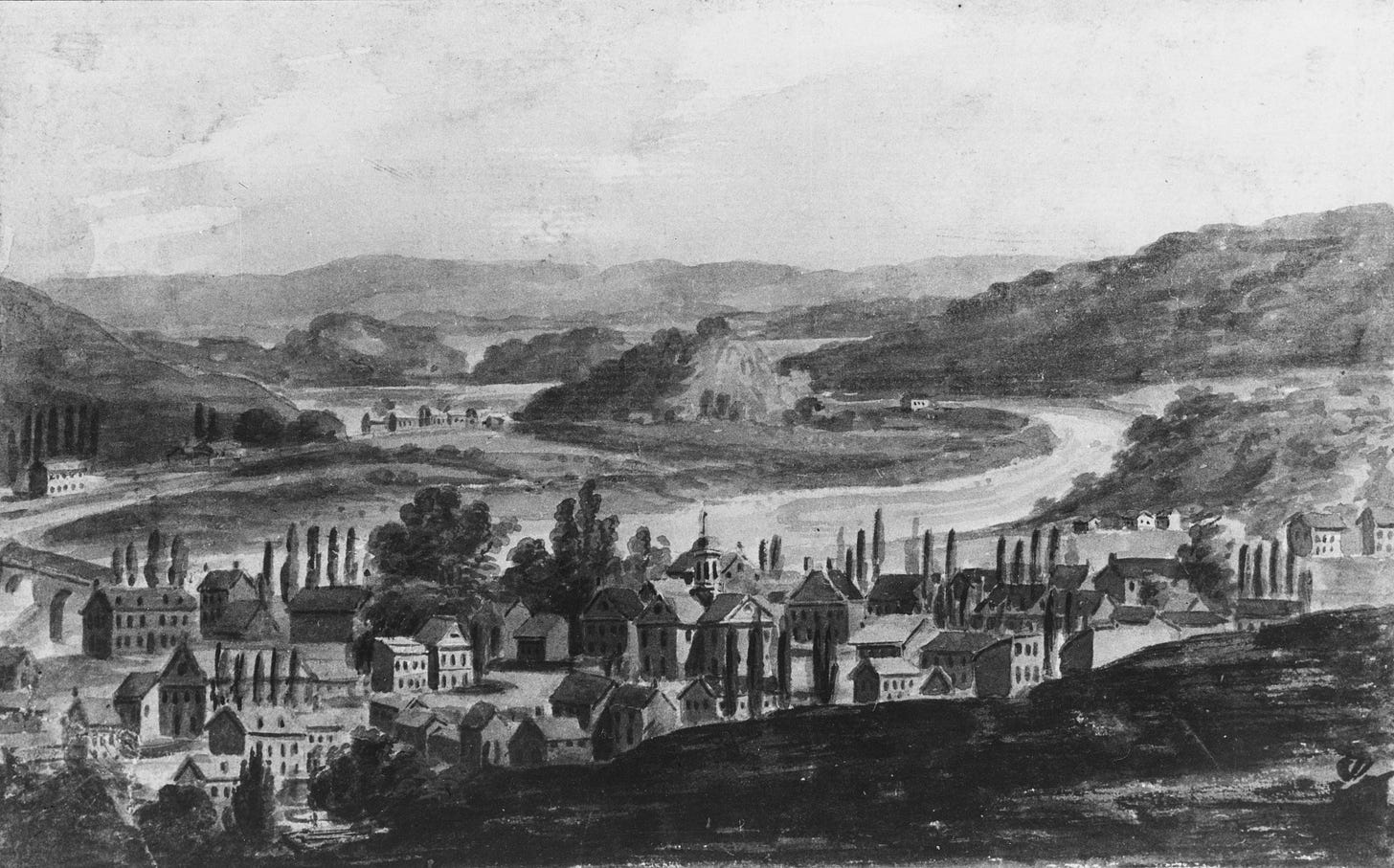

But of course the American Revolution pitted Americans against Americans, dividing families, friends, and neighbors. It was a real war. Anyone inclined to romanticize it could do worse than to read Edmonds’s Drums Along the Mohawk, a historical novel following the course of the war in central New York along the Mohawk River Valley, especially the town of German Flatts, near Herkimer. I picked up the book in a used bookstore earlier this summer, partly because I recognized Edmonds’s name, partly because I’ve driven through the region multiple times in recent years, following I-90 as I took children back and forth to college or law school.

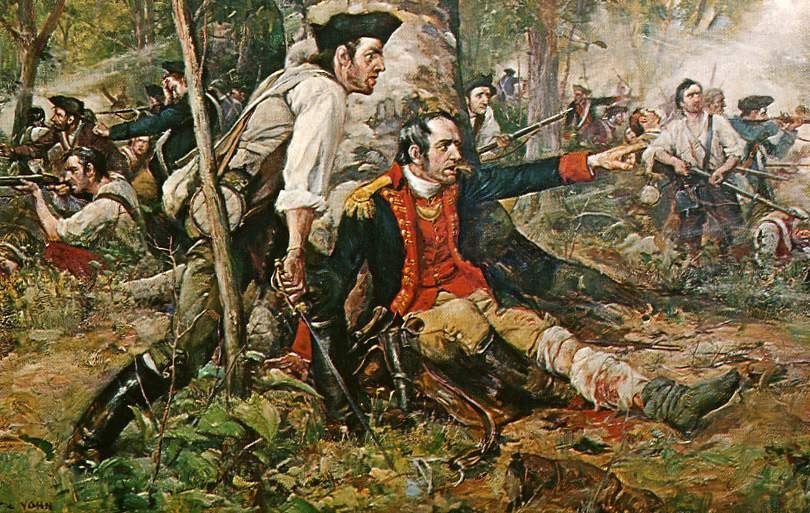

It’s a lovely region, and I won’t look at it quite the same way after reading Drums Along the Mohawk. Edmonds tells the story of a young couple, Gil and Lana Martin, in order to describe events on the western New York frontier during the Revolution, but he sticks close to actual events and includes a large cast of characters, most of them historical figures, such as Nicholas Herkimer, hero of the battle of Oriskany (see painting above), or Adam Helmer, a scout who made a famous 30-mile run, winding over hills and through forests to outpace Indian pursuers and warn the Americans at Fort Dayton of an impending attack.

Edmonds does not deliver a mythic telling of a glorious past, however. To the contrary, his novel does an admirable job of capturing the complexities of the years from 1776 to 1781. The Mohawk valley included Dutch and German settlers, couples like the Martins moving from farther east in search of cheap land they could call their own, British nearby in the Canadian north, loyalists and “continentals” living together in the same communities as tensions rose, and Native American tribes from the six nations of the Iroquois, some of whom fought with the British, others with the rebels.

All this makes it difficult to divide the hostile parties neatly into the good guys and the bad guys, and while Edmonds’s own sympathies lie with the rebels, he does not oversimplify matters. We see a Tory sympathizer wrongly accused of a crime and jailed under dreadful conditions; the “continentals” as well as the Tories commit what we would now call war crimes, burning down villages together with their inhabitants. It is not described in the novel, but at one point some of the men are sent off on the infamous Sullivan expedition, which moved deep into Western New York, destroying numerous Iroquois villages along with all of their crops and driving thousands of Native Americans out of the region. (All this happened very near to where I now live.) One of the young men returns from the expedition looking “not at all like the boy who had started out.” Dazed by what he has seen, he tries to explain it to his new, young wife:

“I don’t know how much we burned. Captain Bleecker figured it out that the army had destroyed one hundred and sixty thousand bushel of corn. The Indians all went west to Niagara.”

“Was there any battles?”

“Only one. It was short. There was five thousand of us and only fifteen hundred of them, more than half Indians. Afterwards they cornered a scouting party. Twenty men. They caught two of them and burned them in Little Beard’s town. Chinese Castle.”

He stopped suddenly.

“Poor John,” she whispered.

“It was mostly just walking,” he said. “Walking every day and sometimes at night. Or burning. Or cutting corn with your bayonet. We got short of food and had to eat our horses. We wished we hadn’t burned everything, coming home…. I don’t want to talk about [those men the Indians burned]. I been dreaming of the way they looked. It makes me afraid sometimes. I don’t want to go to war again, Mary.”

As that passage shows, Edmonds recognizes the considerable brutality shown by all sides—not only what Jefferson in the Declaration called “the merciless Indian savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions,” but the equally merciless violence meted out by the settlers, both Loyalist and Rebel, against each other or against the natives. People like Gil Martin are swept up in this violence, victimized by it as their farms and homes are repeatedly burned, but also becoming part of the machinery of war themselves.

As much as anything, Edmonds helps one appreciate the tremendous vulnerability of the settlers out on the western frontier. Far from Albany or other eastern centers of power, with few neighbors, they are not a priority for those conducting the war, who often leave them largely to fend for themselves (and, when they do provide assistance, follow it up with a large tax bill well beyond the settlers’ ability to pay, especially after losing their homes, crops, and livestock). As the narrator says at one point, “The surprising thing was that so many people stayed at all.” But they do. Partly because they lack better options: “Many of them felt they could not afford to leave. With the destruction of their wheat, their only source of income had been obliterated.” But also out of a stubborn desire to hang onto the land they have begun to wrest from nature and to claim as their own: “Many of them did not want to move. They had brought the land from wilderness to farm…. To abandon their homes would be, it seemed to them, to give up the human right to hope.”

Walter Edmonds is not much remembered today. Most of his works are mainly of regional interest for readers in central and western New York. My own first encounter with him was a light novel called The Wedding Journey, about a newlywed couple who take a journey of a few days down the Erie Canal—an enjoyable read, but not great literature. In Drums Along the Mohawk, however, he manages to imbue the region he knew so well with a larger sense of destiny, showing how the lives of its inhabitants are caught up in events of continental and indeed global scope. But he only gestures toward that broader picture while keeping his focus squarely on the challenges and toils, as well as the dignity, of folks like Gil and Lana Martin. It is a notable achievement, and one that even now, 250 years later, conveys to the reader something of what it must have been like to live through that era far from the centers of power, as America was being born.

One could say more about this long, complex novel—but I’ve got to get to Denver! Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you next week for another installment From My Bookshelf.

I love the map!