It has been a full weekend here in the Meilaender household. Two of our daughters are home for a couple of days, so we have been trying to spend time together while they’re here. And my German father-in-law appears to have had a stroke yesterday, so we are anxiously awaiting more news on his condition; as I type these words, my wife is telephoning with one of her sisters in Germany, our first opportunity to get real information on the situation.

I thus find myself grateful that chapter six in The World of Yesterday, “Bypaths on the Way to Myself,” turns out to be short, without a lot of deep material to sink our teeth into. Its highlight is surely the second half, where Zweig tells the story—so improbably tragic as to be humorous—about three actors dying as they were about to premiere his plays. First Adalbert Matkowsky, then Josef Kainz, and finally Alexander Moissi—all three agree to perform roles in dramas by Zweig. None of them realizes that in doing so he is signing his own death warrant.

This is one of those moments when Zweig the novelist briefly takes over from Zweig the memoirist. He carefully sets up the anecdote-trio by describing his delight at learning that the Prussian State Theater wanted to stage his early verse play Thersites, and that the great actor Matkowsky would play the role of Achilles. But then Zweig offers a warning, almost in the form of a proverb: “Since then I have learned never to anticipate the joys of a première before the curtain finally goes up.” Don’t count your chickens before they’ve hatched, we might say; or, in German, man soll den Tag nicht vor dem Abend loben.

Unbelievably, Matkowsky falls ill on the very eve of the performance and dies a week later. Zweig is devastated, but soon his hopes are renewed: Kainz, a second leading actor of the era, commissions a one-act play from him. “Again it seemed as if I were winning a grand prize,” writes Zweig. “It was almost too much for a beginner.” But tragedy repeats itself: Kainz returns from a tour, falls ill, and also dies before he can perform Zweig’s play. Again Zweig the novelist foreshadows what is to come with an oracular comment: “If one shuts the door upon misfortune it will sneak in through another.”

By now we know what is coming. Zweig prepares another play for the stage, and this time the cast escapes misfortune… but the play’s manager dies. And we aren’t done yet. When Zweig’s friend Moissi asks him to make a translation of Pirandello, we readers are practically shouting, “No, don’t do it!” But he does, and of course Moissi falls sick and dies.

This would be enough to make anyone superstitious, but Zweig dismisses it as “nothing more than chance.” He concludes the chapter somewhat stoically: “It is only early in life that one believes fate to be identical with chance. Later one knows that the actual course of one’s life was determined from within; however confusedly and meaninglessly our way may deviate from our desires, after all it does lead us inevitably to our invisible goal.” Perhaps, although one might hesitate to endorse that in light of Zweig’s own eventual end. The World of Yesterday is a wonderful book, but Zweig is not a great philosopher.

The chapter doesn’t contain a whole lot that we need to discuss (if you disagree, leave a comment!), but it did remind me of a few treats I can share with you here. But before I get to those, here is a quick lightning-round of three very brief observations on chapter six:

While we’re on the theme of Zweig’s limitations as a philosopher, I note that he does comment again, in passing, on the ideal of freedom. He selects a small apartment on the outskirts of Vienna “so that my freedom was not weighted by costliness…. It was also my intention not to settle down in Vienna lest I might become sentimentally bound to a definite place.” Here we see Zweig’s aversion to any dependency, his difficulty with being “bound,” which he associates with “freedom”—mistakenly, in my view. (But if you don’t want to feel sentimentally bound to a place, he is right that you would do better to avoid Vienna! Because the city will capture your heart very quickly.)

Zweig has a fondness for underdogs. Here it comes out in the reference to his play Thersites. Of course Zweig focuses not on Achilles but instead on the Iliad’s loud-mouthed and unpleasant boor. Zweig recognizes this “personal trait in my inner attitude which invariably never champions the so-called hero but rather always sees tragedy only in the conquered.”

When Zweig describes finding a publisher, the Insel-Verlag, it is hard not to be reminded of the struggles that independent presses have today to reach a market for serious and thoughtful literature. “To accept only works of the purest artistic expression in its purest form was the motto of this exclusive publishing house,” he writes. A description of Substack at its best?

And now for my promised treats. In this chapter, Zweig refers to his “autograph collection,” that is, his collection of original manuscripts—a musical score from the hand of Beethoven or Mozart, a page of handwritten manuscript from Balzac. Zweig’s collection of autograph manuscripts was in fact superb. When he went into exile, sadly, he was forced to part with much of it. A significant portion of it is now held by the British Library, to which his heirs donated it; I have seen some items from it on display there in the past.

The collector’s enthusiasm shines through when Zweig describes the special attraction exercised upon him by an original manuscript in the author’s own hand: “That mysterious moment of transition in which a verse, a melody, emerges out of the invisible, out of the vision and intuition of a genius, and is graphically fixed in a material form—where else can it so well be examined and observed as in the tortured or trance-born manuscript of the master?”

I don’t own any original manuscripts like Zweig’s, but I do have a few books that have reached me after passing through the hands of more illustrious owners. I thought I might share three of them with you here to round out today’s post. All three happen to have an Austrian connection.

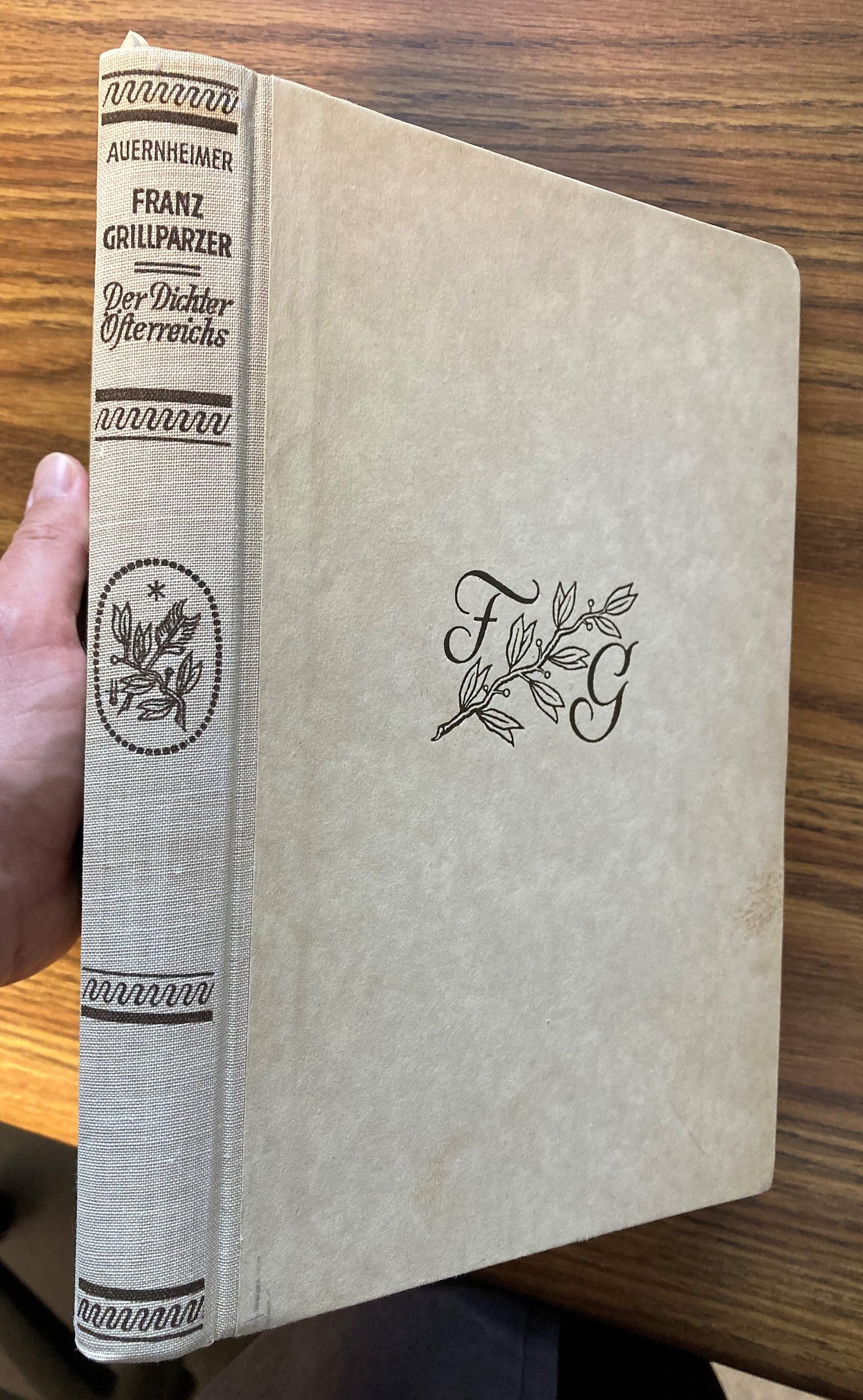

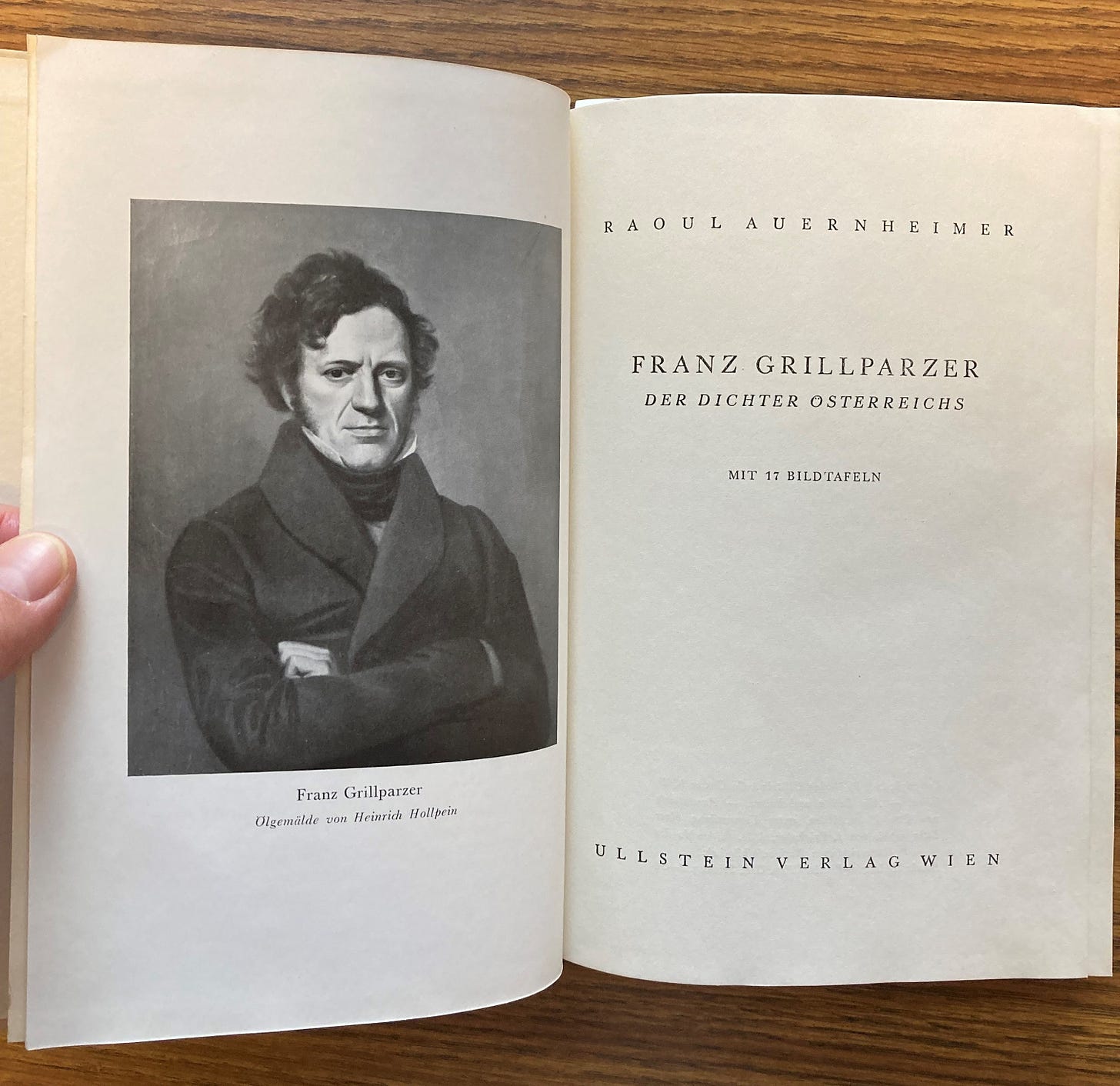

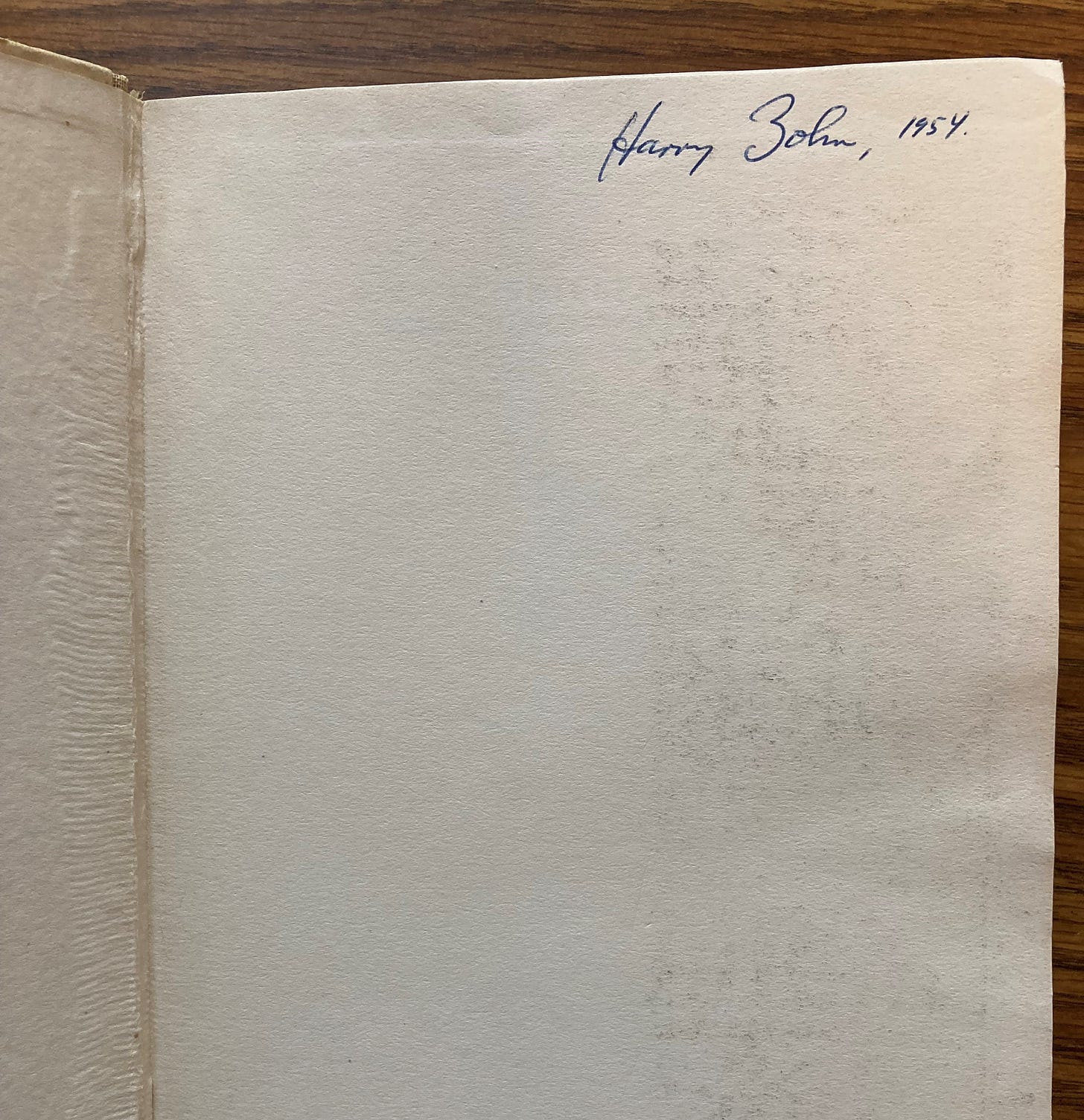

First is a book that can claim a distant connection to our read-along. Harry Zohn was a leading scholar of Austrian Studies. In the same class for which my students are reading Zweig, they will later read an abridged version of Karl Kraus’s play The Last Days of Mankind in an edition prepared and translated by Zohn. In fact, my copy of The World of Yesterday includes a short introduction by Zohn.

In my office I have a book about the Austrian poet and dramatist Franz Grillparzer. Written by Raoul Auernheimer and published in 1948, it is titled Franz Grillparzer, der Dichter Österreichs (The Poet of Austria). When you open the book, on its very first blank page, opposite the cover, is a previous owner’s inscription: “Harry Zohn, 1954.” Most of you will not get terribly excited about a book previously owned by Zohn, but for me it’s pretty neat.

With my second example, we move into somewhat more elevated territory (with all respect to Zohn). Many of you will have heard of the important twentieth-century sociologist Peter Berger. Berger was actually born in—you guessed it—Vienna in 1929. He emigrated to the United States after the Second World War. He is probably best-known for a book on the sociology of knowledge that he co-authored with Thomas Luckmann, The Social Construction of Reality, and he also did important work in the sociology of religion.

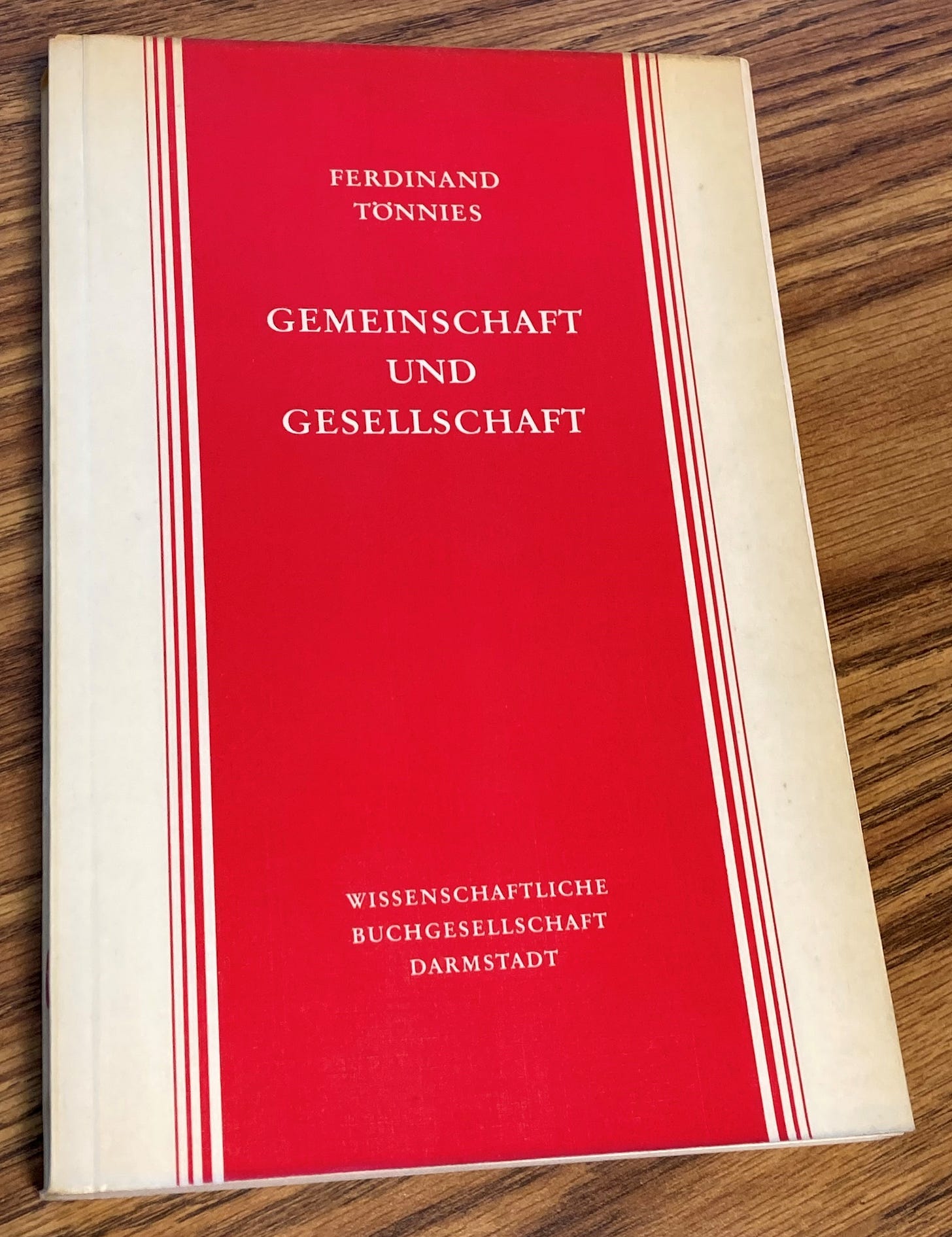

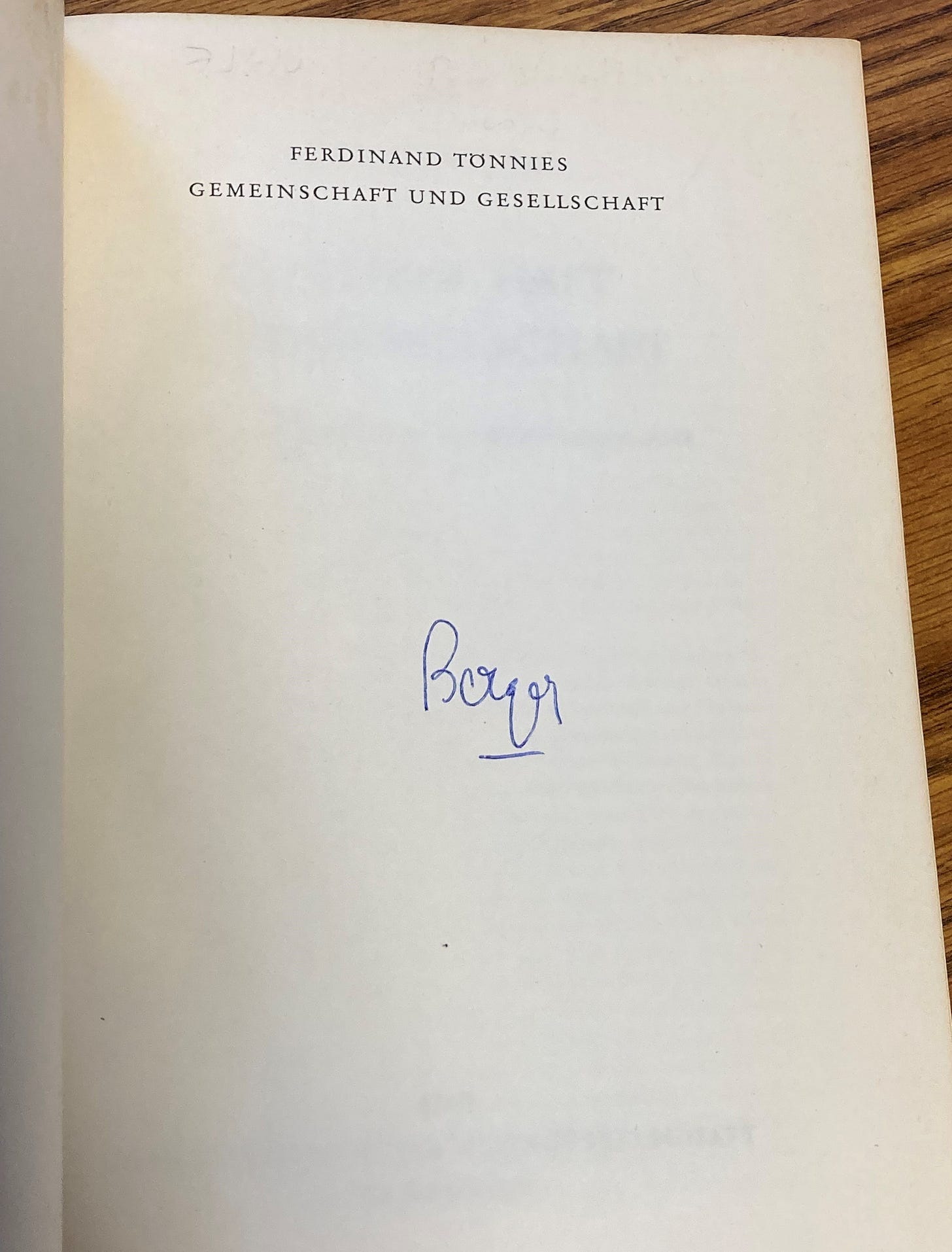

Among Berger’s most famous sociological predecessors was the German Ferdinand Tönnies, who lived from 1855 to 1936. His most famous work was Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft, in English Community and Society, a study of two contrasting forms of community, one traditional, the other modern. I own a German edition of Tönnies’s classic, and it too has an inscription on the first page, a single, underlined word: “Berger.” It came from Peter Berger’s library. So I have a copy of one of the great classics of sociological theory that was owned by another of the great sociologists. My one disappointment: no marginalia.

And now for the third example, the neatest of all. Probably few of you are familiar with the Austrian author Peter Rosegger. He lived in the province of Styria, in southern Austria, from 1843 to 1918. He was extremely beloved and extremely prolific, authoring many novels, short stories, and poetry, often describing rural Austrian life. For almost four decades, he also edited an almanac entitled Heimgarten. Long-time readers of From My Bookshelf might remember that last year, during Advent, I translated his short story “The First Christmas Tree in the Forest Home” and shared it here. (If you are interested, here is part one; and part two; and part three; and part four!)

Perhaps a few more of you have heard of the Wittelsbach dynasty, whose various branches ruled Bavaria and neighboring territories for many centuries, their rule ending only with the First World War. The final queen in their line—the last queen of Bavaria—was Marie Therese von Österreich-Este.

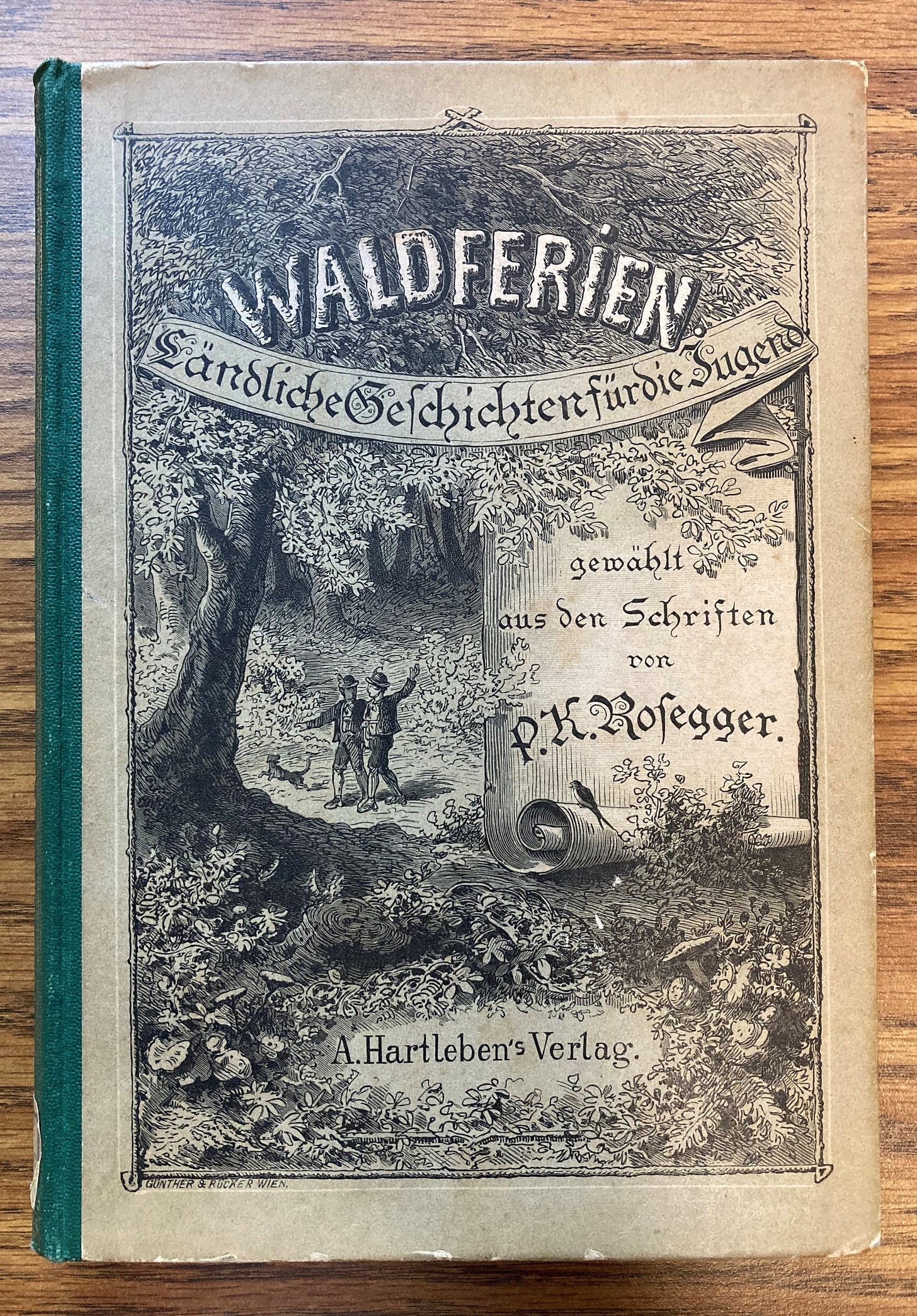

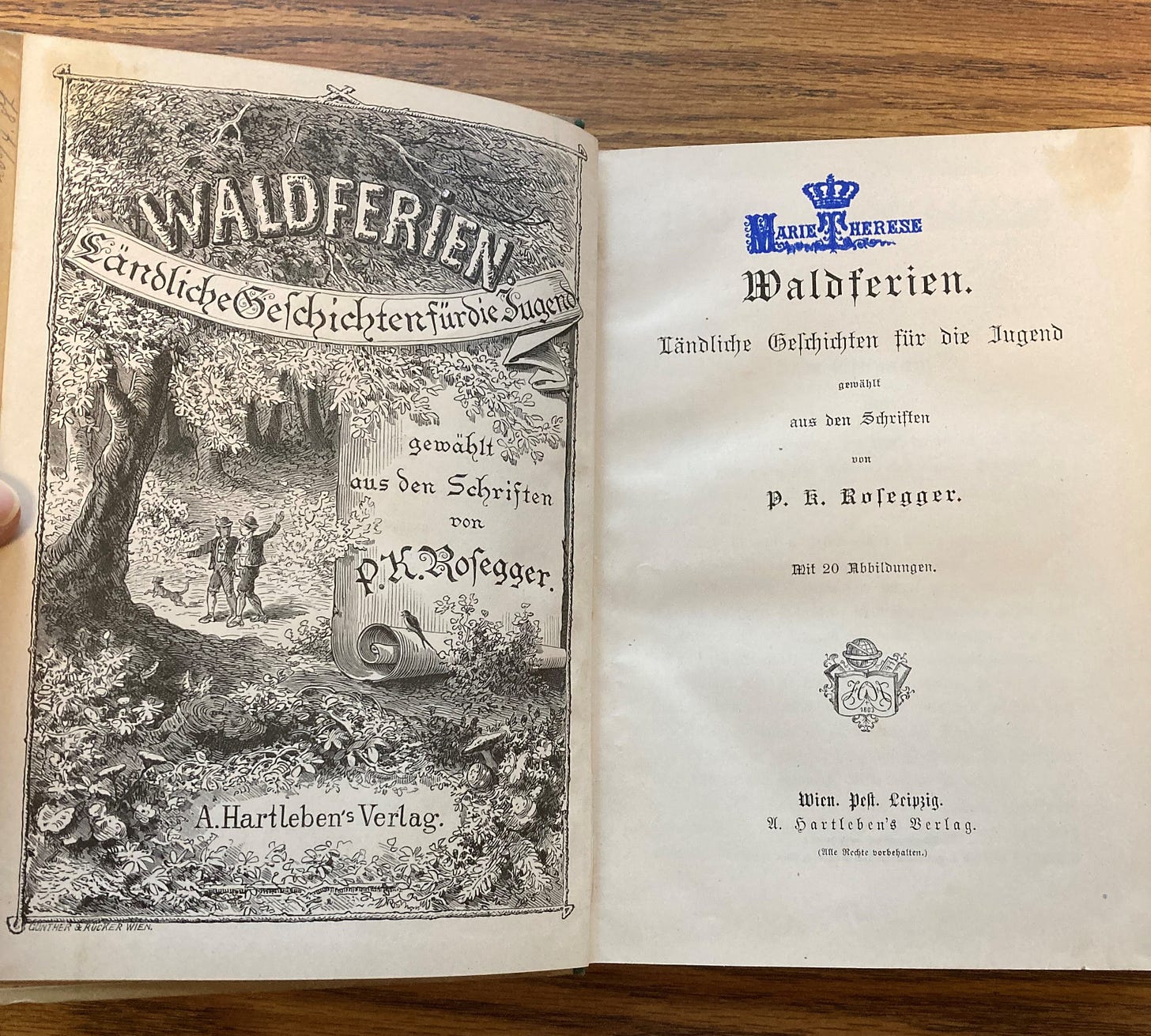

And thus we come to the crowning glory of this post. I have a copy of a small book by Rosegger, published in 1887, entitled Waldferien, “Forest Holidays.” It is a collection of short stories and poems. Here is a picture of its attractive cover.

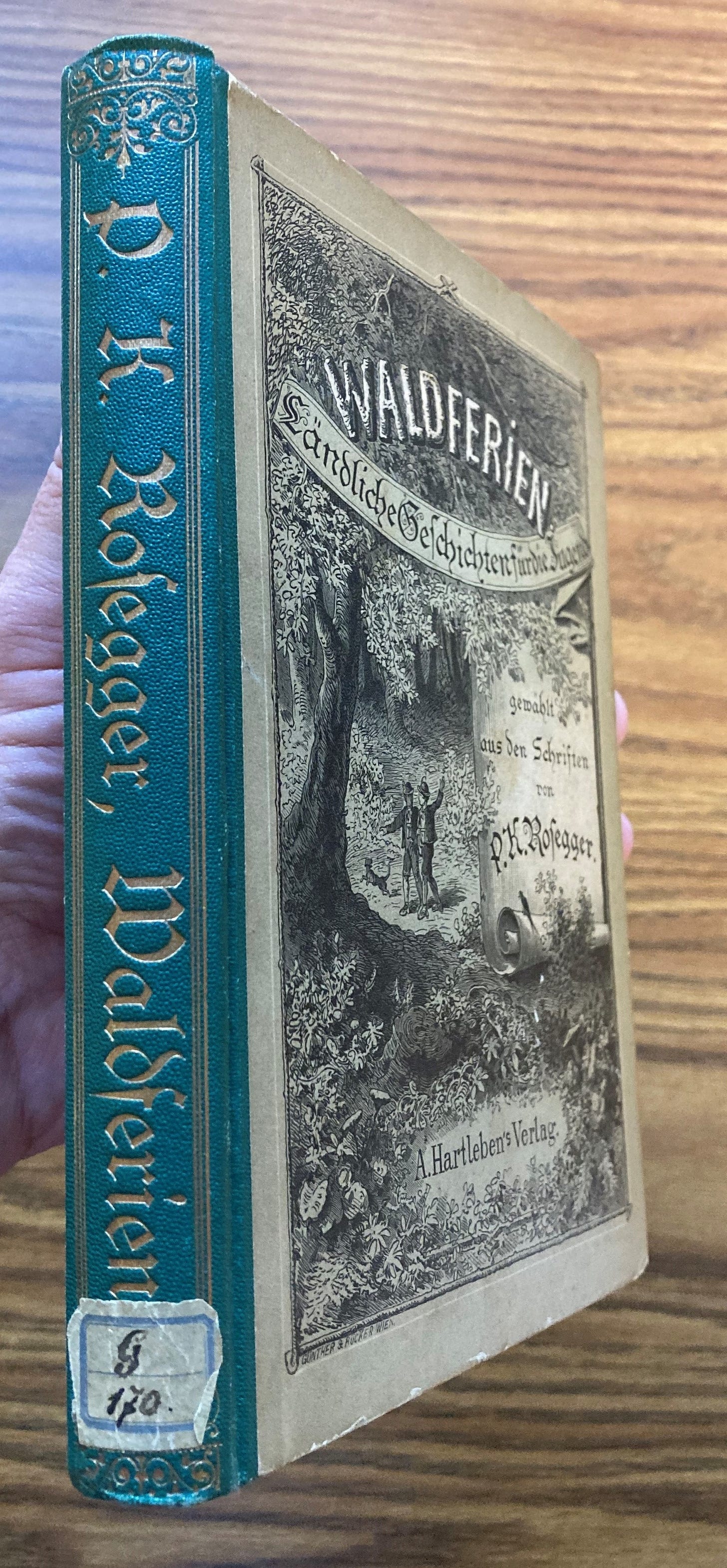

At the base of the spine is a small sticker, indicating the book’s previous location in a library cataloguing system.

But from whose library? As it happens, the title page has been stamped impressively by a previous owner, and the stamp sports a crown.

Yes, that’s right: it says “Marie Therese.” The book comes from the Wittelsbach library—and from Marie Therese, last queen of Bavaria.

Rosegger’s Waldferien: from the last queen of Bavaria to my bookshelf. For a bibliophile, Germanophile, and Austriophile, it doesn’t get much better than that. I bet even Stefan Zweig would have been just a tiny bit jealous.

As always, thanks for reading, and I’ll see you next time for another installment From My Bookshelf.

I remember Rosegger from your Advent post; apart from that, I've not read any of his work. Which of his novels would you recommend as a starting point?

Sometimes, serendipity leads to a prepared mind. As I was preparing to travel with my wife to Vienna to celebrate our anniversary, I came upon the Substack series about Zweig's book, which led me to read The World of Yesterday before beginning my travels.

Both the book and Substack have enriched our time in Vienna. When we visited the Leopold Museum, I came upon numerous references to Zweig, and an exhibit bearing his photo and this description:

"The writer Stephen Zweig was a cosmopolitan and a convinced European, but remained a lifelong representative of the spirit of the late Hapsburg empire. His extensive work is governed by a pacifist-humanistic mindset. His greatest international successes were his biographical novels."

Thank you for your fine Substack articles.