On Monday, 21 April 2025, the world mourned the death of Pope Francis. (See my post from last August about the pope’s letter on literature.) But it turns out that on that same day another person worth remembering also died: Peter von Matt. Though his name is not widely known to English readers, von Matt was Switzerland’s greatest living Germanist or scholar of German literature—perhaps the greatest living Germanist, simply. A brilliant reader, great scholar, superb prose stylist, and captivating speaker, von Matt was also a warm, kind, and generous man.

For about the past fifteen years, my academic work has been largely on political ideas in German-language literature, primarily from Switzerland and Austria. This is, at best, a rather niche specialty for someone whose degree is in political theory. During that time I have been fortunate to receive encouragement from three outstanding older Germanisten. The first was Hanns Peter Holl, for my money the finest interpreter of the 19th-century Swiss author Jeremias Gotthelf. When I first became interested in Swiss literature, and in Gotthelf specifically, I spent a brief weekend in Bern and, at a relative’s suggestion, got in touch with Holl, who taught there at the university. He met me at my hotel and then spent the next few hours walking me around the city, pointing out various locations connected to Gotthelf, and inviting me to lunch. He encouraged my notion that studying Gotthelf as a political thinker made sense.

The second of these scholars was Jürgen Hein, a specialist in Ferdinand Raimund, Johann Nestroy, and the old Viennese “Volkstheater,” popular theater. Hein was among the editors of the critical edition of Nestroy’s works. When I applied one summer to present a paper at the annual meeting of the Nestroy Society, he extended an enthusiastic invitation and gave me a warm welcome. Like Holl, he seemed to find nothing strange in a political scientist’s busying himself with these literary texts.

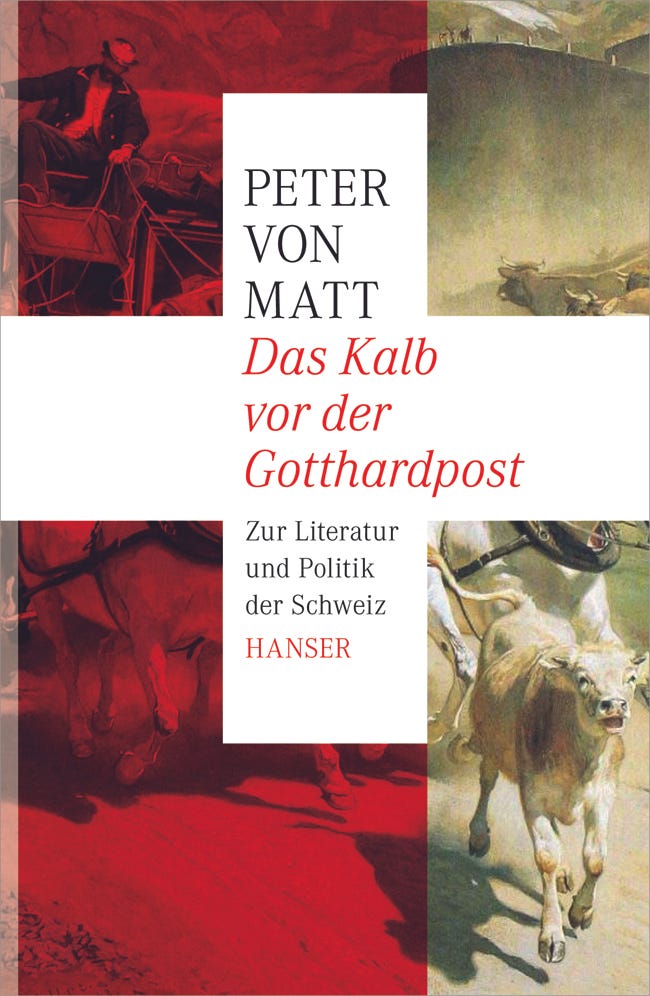

Peter von Matt was the third of these scholars who graciously encouraged me. In the summer of 2012 I spent seven weeks in Bern, doing research on Gotthelf. I knew of von Matt’s name but had read none of his work. Browsing the bookstores, I saw his newest book, which had only recently appeared, a collection of essays on Swiss literature, Das Kalb vor der Gotthardpost. I bought it.

And was entranced. In clear prose, utterly free of academic jargon or obscure theorizing, von Matt found new insights in everything he touched. The volume opened with a long, 100-page essay that gave the book its title, “The Calf Before the Gotthard Mail Coach.” (The essay also has a secondary title: “Switzerland Between Origins and Progress: On the Spiritual History of a Nation.”) The title refers to an iconic 1873 painting by Rudolf Koller, which appears on the book’s cover and shows a calf fleeing the onrushing Gotthard Pass mail coach.

The title essay is a minor masterpiece. (And—like the similar opening essay in von Matt’s earlier collection, Die tintenblauen Eidgenossen, it deserves publication in English translation. If any enterprising publisher reads this and wants to give it a whirl, I would be eager to make these superb essays available to English readers!) Von Matt dances through an expanding Swiss literary canon, weaving his observations together with history, philosophy, art, theology, politics, and anthropology, as if the boundaries between these disciplines had melted away. It is a kind of humanistic writing that is increasingly rare in our specialized age. Von Matt wears his learning lightly, but his ability to weave such a broad tapestry is breath-taking. One comes away with a richer understanding not simply of Swiss literature, but of Switzerland as a whole, and even of Western modernity.

As soon as I read it, I thought to myself: this is the kind of essay I would like to write, if I could write as well and were as learned as Peter von Matt. (Very few can, and very few are.) Many other readers clearly shared my enthusiasm, since Das Kalb vor der Gotthardpost won the 2012 Swiss Book Prize—still the only work of non-fiction to have won the award.

Von Matt’s 2012 prize became the spur for our first encounter. For a number of years, a colleague and I led an interdisciplinary “Swiss Studies Network” within the German Studies Association, a professional association for scholars. With support from the Swiss Embassy, we invited von Matt to participate in a seminar honoring his award and exploring his work. To our delight, he accepted, and I got to meet him in Kansas City in the fall of 2014. He was everything we could have hoped for: he had read all our papers in advance and responded to them with wit and grace. For the most part, of course, we were complimentary. One colleague, however, did take him to task, rather persistently, for having paid too little attention to women authors in his work. Instead of becoming defensive or hostile, von Matt—whose wife Beatrice is a highly regarded literary critic in her own right—lowered the temperature with a disarming response that combined humor, humility, and candor. “You have to understand,” he said, “that when a publisher wants a foreword to a book by a male author, they ask me. When they want one for a book by a female author, they ask my wife.”1

I had another opportunity to meet von Matt about a year or so later, when I was again in Switzerland briefly over the summer. When I traveled to Zürich for a couple of days, I contacted von Matt and asked if he was free. He met me at my hostel and proceeded—as Holl had earlier done in Bern—to walk me around the city. He took me past the house where Gottfried Keller was born; he showed me the grave and statue of James Joyce in the city’s Fluntern Cemetery; he pointed out the memorial to Georg Büchner. He bought me lunch, discussed Jeremias Gotthelf, asked about my family. As in Kansas City, he was engaging, kind, and encouraging.

I was then and still am both impressed and touched that von Matt, one of Switzerland’s most popular speakers and always in high demand, was willing to take time like this for an American political theorist dabbling in Swiss literature. I met him in person on only those two occasions, but both times I found that his kindness matched his learning and his wisdom.

Von Matt was a Swiss patriot and a committed European, an accomplished scholar who could captivate a broad public, a literary traditionalist who enjoyed and promoted new voices. His creative intellect, revisiting beloved works of literature, probed them from new and surprising angles, producing books about faithless lovers, wayward children, skulduggery, and literary kisses, as well as his studies of Swiss history and identity. He never seemed to run out of ideas.

I wish I could write essays the way Peter von Matt wrote them. I’m sorry he won’t be writing any more. But what a gift to have the ones he has left us.

As always, thanks for reading, and I’ll see you next time for another installment From My Bookshelf.

The seminar gave rise to a collection of essays that I co-edited along with Hans Rindisbacher, Writing Switzerland: Culture, History, and Politics in the Work of Peter von Matt. Oddly, this volume has never become a best-seller.